Cyberterreiro

Text by Gil Amâncio

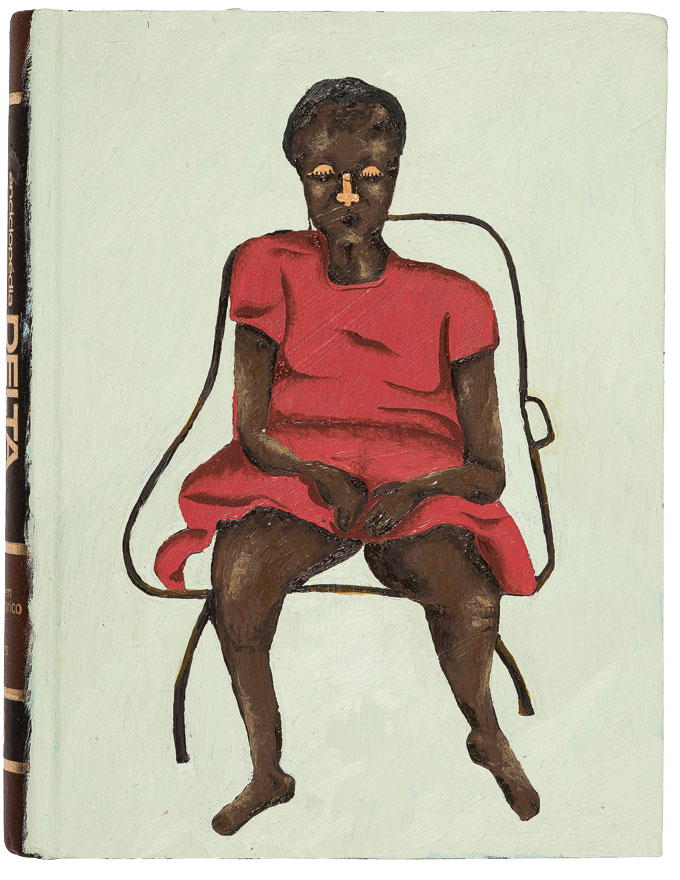

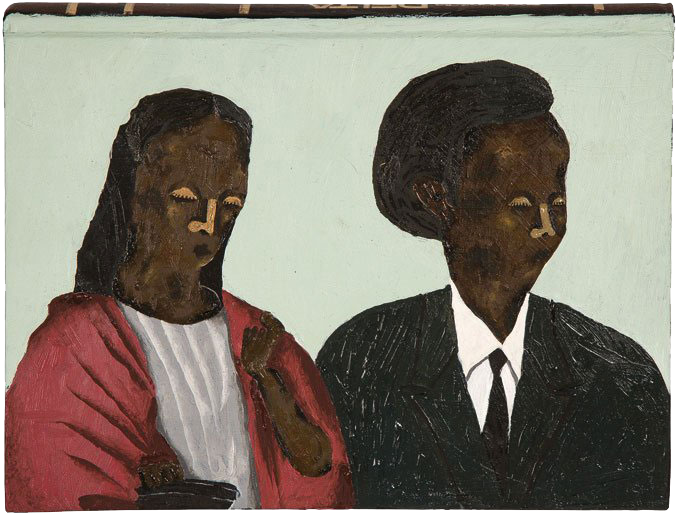

Retrato silenciado, paintings by Dalton Paula

The Portuguese sought in Africa specialized labor and technologies that they simply did not master. Now, we need to work on archeology, on personal memory. It is up to us to hack the colonial codes with our ancestral devices.

An important principle for the diaspora is the consolidation of terreiros(1) as a way of grounding our knowledge physically and symbolically. Recently, as I looked at my backyard, I observed how I was settling in it all the knowledge which, over many decades, I have become aware of and with which I have created and invited other artists to create. As I fed on Afro-diasporic knowledge, I was creating movement in that space and increasing its strength of attraction. Another important principle for the African diaspora is the spiral movement, the whirlpool. A movement that activates the force of attraction, which, for us, is always a calling.

In 2007, I transformed my backyard into NEGA,(2) the Experimental Group of Black Art and Technology. When you enter it, you see a wooden sculpture made by Mr. Rubens, an ogan(3) who lives in the neighborhood. One day he asked me if I wanted to buy a sculpture he had made – a preto velho,(4) a way of remembering the presence of our ancestors from the Black Atlantic. Some time passed, and Mr. Rubens came with the figure of an Indigenous person, to remind us of the Indigenous peoples, the owners of this land that we now call Brazil. In the same yard, at the back, near the banana trees, symbols of the constant recreation of life, there is a sculpture of a woman, also brought by Mr. Rubens. It represents the female ancestral power that guarantees life.

I occupied the shed next to my house with tools for creating, recording, and connecting with the world – computers, musical instruments, books, videos, CDs, hoes, hammers, pliers, and saws. We didn’t want to use technology as a scenic effect, we wanted to create a language that produced enchantment. How would Black artists appropriate these tools?

It all starts with a simple dot

But a dot alone does not enchant

It takes several dots to form a line.

And several lines form a crossed-out line.

A text about Os Pontos Riscados da Umbanda was the inspiration to make the connection between hip-hop and the culture of the terreiros. At that moment, the VJ was appearing as a figure who produced images that interacted live with the music played during parties. The VJs were a result of the development of new digital sound and image technologies that allowed people involved in audiovisual production to perform maneuvers with images that were similar to those the DJs would perform with sound.

NEGA thus inaugurated its vocation as a space for creation and, at the same time, for training. We were creating a new language and also training artists to think about possibilities for transposing the language of urban dance to the stage, as well as the use of new digital sound and image technologies and the connections between hip-hop and Umbanda.(5) We worked with the Toonloop software, which enabled the relationship between the dancer and the visual artist. Along with urban dances, we brought the stories of the Orixás(6) to the backyard as told by Black bodies. We had to study the stories, rhythms, and dances of each Orixá and then also research the dance styles of each of the male and female dancers to see which dance style best expressed the character of each Orixá.

Thus, the Black Horizonte Collective started in my backyard, as a pun with the name of the city Belo Horizonte, expressing our desire to darken the city. In 2011 I started to invite Black men and women friends to eat dried meat farofa,(7) drink some cachaça,(8) and talk about the production of Black art and the spaces run by Black people in the city since the end of the 1990s. One day, during a rehearsal, looking at the backyard and seeing all those computers, speakers, drums, and controllers, I said: This looks like a cyberterreiro!

I realized that NEGA was building from the terreiro its knowledge and identity, and thus it gained its oriki – a name-poem in constant transformation. Cyberterreiro is an open, expanding concept-action, a dive into Afro-diasporic arts and cultures. A transient territory where the production and transmission of knowledge takes place based on performance and sound bodygraphies that use ancestral codes to hack colonial codes.

Our backyard was afro futuristic! Not in the sense of the use of digital technologies, but in the sense that we were having the opportunity to experience life based on the ancestral knowledge that made it possible for African men and women and their descendants to survive the crossing of the Black Atlantic – as Paul Gilroy put it in his book. With that knowledge they had created strong institutions such as terreiros, brotherhoods, quilombos(9) and favelas,(10) which keep our arts alive to this day.

My father was called Thomaz and my mother is called Gabriela. The experiences I had during my childhood with my parents and relatives, the festive atmosphere, and the ever-present singing contributed to my musical formation. Zé Grandioso, my uncle, had a truck. Together with another uncle, Zé Amâncio, they used to stop by our house and serenade my mother. We woke up to singing and mom would make coffee for everyone. After the serenade, we would get on the truck and go to another relative’s house, where everyone would get off, sing and drink coffee or cachaça, then get back on the truck and continue with the pilgrimage. It was a party!

When my uncle Zé Amâncio would come to our house and play the guitar, I would assemble a drum kit with my mother’s pots and go play with him. Since then, every time he came to my house to play the guitar, I would hear: “Call Gilberto with the pans!” My father also enjoyed playing the guitar and, later, the violin. He inherited this from my grandfather, Thomaz, who in addition to playing the guitar, loved the circus. When he was young, my father learned how to work with wood with his uncle Zé Nabor and he then built his own guitars and violins. When he got married, he left art aside. In my family, I am the third generation of those attracted to art and the first to have art as a way of life.

My father was very serious and systematic, but he could suddenly turn into someone else. He would disappear and then came back into the living room with a straw hat falling over one side of his head and a shabby jacket, and he would make us laugh, full of grimaces… My brothers and I laughed a lot, sometimes we made fun of him, and we were embarrassed when there was someone in our house. Years later, when I went to a Congado,(11) I could see that the body gestures my father used then were very similar to the way congadeiros(12) danced. What my father did was rooted in the Congado tradition. It somehow got into my family. There is a theatrical form of ours, a form that I saw in my father and that we find, mainly, in our elders. It is a theatricality that we rarely study or explore. Grande Otelo(13) knew how to use this body style very well as a language of Black theater to be investigated; however, it is not yet part of our training.

In 1979, a ship landed in Belo Horizonte. A queen would come down and evoke her warriors for the creation of an urban quilombo: Marlene Silva’s Afro-Dance Academy. Marlene brought the Afro-dance movement to the city and, to the artists and intellectuals who were close to her, she brought the need to know and research. Afro-dancing required vigor. It required dialogue between the dancer and the drums. It demanded a rhythmic precision that was not part of the training of classical and modern dance schools. At the same time, it also demanded musicians prepared for the appropriate execution of the songs.

During rehearsals, we’d hear Al Jarreau’s vocal percussion; the sound of congas(14) by Mongo Santa Maria, Sheila Escovedo, and Naná Vasconcelos. We listened to the percussive music of Marlos Nobre, the Congado, the Maracatu(15) of Chico Rei de Mignone; and by researching we could learn about the rhythms, dances, songs of the Orixás and guards of Congo and Mozambique.(16) At Marlene Silva’s Academy, I reconnected with Black culture. Before that, I still carried strong values from my Catholic upbringing and from working in the church’s youth movement. I also had some involvement with Asian culture through meditation and nutrition. I had ended up, with all that, distancing myself from the Black universe.

At the Afro-Dance Academy, among Black men and women, I remembered my adolescence and youth, when I used to dance to James Brown. I was able to go for the first time, taken by Marlene Silva, to an Orixá outing.(17) It was an inexplicable emotion. The beauty of the clothes, the songs, and the movements… That experience was decisive in awakening in me the desire to know more about the universe of Candomblé, terreiros and Reinado(18) festivals. Those were meeting places where Black artists and intellectuals talked about Black art and culture, stimulating the emergence of contemporary Black music and dance in the city.

With one foot in the performing arts and the other in the terreiro, I closely followed the contemporary art debate. At the Orixá outings, I found what many artists were looking for. I saw bodies that would recreate, with movements, the narrative of African myths, establishing a deep connection with the musicians, with the space and with the people present in the ritual. The setting was fully integrated into the dynamics of the ritual and the vocalization of the texts was marked by a musicality between singing and speaking. What contemporary art was looking for was there, right in front of me!

I then began to problematize official art history and focus on Black music production and its connection to the counterculture movements that emerged in the Americas as a result of the enslavement of African peoples. From my research about the terreiros, I started to know the other side of the terreiros, to realize what was happening there musically and in the field of dance. I immersed myself in the universe of the sounds of the atabaques,(19) I learned to identify the ways of playing the drum and the different songs. There was a song for Xangô,(20) and another for Ogum.(21) I identified the relationship between percussion and dance, I came to know the Brazilian rhythms that were not played on the radio or television.

Basic things in my training had been denied to me. When I proposed a type of dance that for me was knowledge inscribed in the body, it was common for someone to treat it as intuitive, sensorial, emotional, or primitive. At that time, when asked about my education, I used to say that I was self-taught. I realized, however, that by acting like that I was denying my own path and the learning process I had within my family, in the terreiros, in the Congados. Claiming to be self-taught, I was saying that I had taught myself everything I knew. Now, that assessment was based on the standards of the so-called erudite or classical culture, European-based. That could not be my reference.

Mr. Raimundo Nonato, Congo king(22) of Minas Gerais, contributed a lot to my reviewing of the idea that I was self-taught. It was in my dialogues with him, a wonderful person, a great artist that I had the chance to meet, that I questioned this definition. I always remember the day I went to meet him for the first time. Sitting on his porch, he asked me if I really wanted to learn to sing. As I was convinced of my affirmation, he called me in and asked his wife, Mrs. Custódia, to prepare a pot of beans with flour and rice. After everything was ready, he took me to the backyard. There was a log where we sat. Mr. Raimundo told me that was the place he liked to sit down to eat. We sat, ate, and talked. Only when we had finished eating did he begin to sing, one song after another, each more beautiful than the last. I remember so perfectly that when I sing today it’s as if Mr. Raimundo Nonato were here teaching me how to sing: “Eh… when I sit under the ngoma tree… Eh…”

His voice was a bit hoarse and nasal. With him, I discovered different sounds. When I was a child, my references were the voices of Cauby Peixoto, Nelson Gonçalves, Ângela Maria, Elis Regina, Gal Costa, Milton Nascimento. Those beautiful voices were clean and clear, which, for the work I wanted to do, did not help. I needed other vocal textures, and I found them with Mr. Raimundo Nonato, sitting in his backyard with a little bowl of beans, rice and farofa, teaching me to understand the sound of Congado and the way they sang. Since he didn’t formalize our meetings as “vocal technique workshops”, I never remembered to put him on my CV. Today I know that my vocal expression is directly related to all the hours I spent with that great master.

When Mr. Raimundo asked if I wanted to learn to sing, he didn’t look for a singing method or say that he would teach me how to sing. He simply sang. Today I see that his performance told me: “I am the singer, listen to me, see how I do it.” He was betting on the transmission of knowledge that way. The dimensions that he wanted to pass on to me could never be transmitted only through writing. Eating that rice and beans, sitting on the log in the backyard under the afternoon light is very different from picking up a text to read in a classroom. The sound he made was related to the place.

I noticed something similar in my research. I would talk about Congado, Candomblé, or other Afro-Brazilian cultural manifestations, I would immediately ask questions, but the people I was interviewing would divert the subject. They invited me to have coffee or to accompany them to the garden. This always seemed pointless to me; I was desperate, I wanted to know about music and not about their gardens! Nowadays, I have realized that the way to reach something is not necessarily linear. What they were doing lacks the dryness and objectivity of scientific research. There is an interest in first knowing who you are, and where you are. There is a whole ritual for transmitting knowledge, and if you don’t go through it, it doesn’t work!

It took me a long while to realize all the knowledge that Mr. Raimundo had transmitted to me so naturally, at every meeting we had. Today I am very attentive to these situations that are not socially recognized as teaching/learning. I am definitely not self-taught. It is my duty to name my professors. To name the people I met on my way and who opened all my senses to perceive the world differently.

I began to imagine another possible place in the art scene. A place that was closer to the way of congadeiros, partideiros, and capoeiristas of making art. The place of the “performadô/performadêra”,(23) a term proposed by Ricardo Aleixo(24) to refer to the performer in Afro-Brazilian culture, whose characters are hybrids and inhabit the crossroads.(25)

We have a specific way of learning and we need to talk about it in schools. There are centuries of classical music there! We need to talk about this among ourselves, Black men and women, who often do not consider our mode of knowledge transmission as valuable. We need to speak of the Afro-diasporic universe not as a place for the exotic, the folkloric, but as a producer of sophisticated aesthetic experiences, based on the rescue of our memories as urban Black people. I realized that it was necessary to work on archeology, on personal memory. We would have to improvise based on what we remembered from family parties, samba circles(26) at friends’ houses, and balls. It was necessary to look at the art produced by groups from the periphery. People who talked about their everyday life, their way of life.

In the late 1990s, I got closer to rap music. Young people wanted percussion and body expression lessons, but they only listened to rap. Dialogue was becaming impossible, so I decided to listen to the rap they were listening to. I noticed that they mixed electronic sounds with the berimbau(27) and samples of vocal groups from South Africa. I began punctuating these references and showing that the guys they liked listened to other things too. Then everything changed. We started listening to African music, like repente or coco de embolada, and they identified these rhythms in rap. We started talking about poetry. If, on the one hand, they were willing to discover another musical universe, on the other hand I began to discover the musical and poetic richness of rap.

To record a rap album in those years, the DJ would create the electronic bases, invite musicians to play the bass, and then the rapper and their group would go into the studio to add the vocals. The whole process was separate. When I was invited by NUC, Negros da União Consciente, to do the musical production for their album, I proposed that we involve the already existing musicality in the community itself – instead of working exclusively with electronic bases. The NUC and I then invited the Capoeira group from the neighborhood to play the percussion bases; the group Meninas de Sinhá to sing nursery rhymes as back vocals; and Trio Senzala to play samba.

Renegado, composer and rapper of NUC, came to my house one day. I showed him the computer I used to make music, and he was so fascinated that he bought a computer too, paid in 36 installments, and built a recording studio in the shack where he lived. I went there almost every day, we talked about music production and softwares. We experimented using different rhythms from Brazil and the world.

In Brazil, we have what we call Afro-dance, but when asked by African men and women about what this Afro-dance is, and what country it comes from, we don’t know how to answer. We have been denied access to information about our own history. The sociological, religious, and political approach of our production ended up leaving the aesthetic and economic discussions that involve the African cultural production of the diaspora in the background.

When she was in Brazil in 2003, Sheila Walker presented me with her book African Roots / American Cultures. In the book, she talks about the transfer of African technologies in the fields of mining, agriculture, care for oneself and others, cooking and the arts, promoted by the enslavement of African people. Based on her research, she traces the routes from which enslaved people came and where they went. For example, the people who came to the state of Minas Gerais were those who, in their lands of origin, worked in mining and had knowledge of iron and jewelry creation. The same happened with agricultural production: the book shows that the cultivation technology of rice is African.

Mateus, my eldest son, introduced me to the book African Fractals, by mathematician Ron Englash. In it, the author shows that great European mathematicians became innovators in the field thanks to the appropriation of advanced knowledge present in African cultures. In Africa, fractal mathematics was already present in the structures of building villages, designing hair braids and composing music.

Accustomed to hearing the story that the Portuguese needed labor and, as they were unable to enslave the Indigenous people, they sought out Africans for manual labor, Sheila draws our attention to another reality. What they sought in Africa was specialized labor and technologies that they simply did not master. Now, it’s up to us, through the transfluency(28) rituals master Nego Bispo(29) talks about, to hack the colonial codes with our ancestral devices.

–

Gil Amâncio is an actor, dancer, musician, and researcher. His combined work as an artist and educator is focused on the formation of new generations in his Cyberterreiro, drawing on the practices of Candomblé, Umbanda, Maracatu, and Capoeira Angola, all rooted in the territory and epistemologies of these Afro-Brazilian traditions. He holds a Doctorate through Notable Recognition titulation in Education at UFMG and is now a professor at UFMG.

Dalton Paula is a visual artist who had participated in Mestizo Histories Exhibition, in 2ª Chongquing Biennal and 32ª São Paulo Biennal, among others exhibitions in Brazil and abroad. He lives and works in Goiânia, Brazil.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in the book Terra: antogia afro-indígena (PISEAGRAMA + UBU, 2023) and translated into English by Brena O’Dwyer.

How to quote

AMÂNCIO, Gil. Cyberterreiro. PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, December 2023.

Notes

1 Terreiros are Afro-Brazilian temples in Umbanda and Camdomblé, Afro-Brazilian religions, where the cults and ceremonies are held. Terreiro is also a word for backyard.

2 In Portuguese: Núcleo Experimental de Arte Negra e Tecnologia. The acronym is a word play with the word “black” in Portuguese.

3 Ogan, in Candomblé, is the name of a person chosen by the ancestral deities, who does not go into a trance, but still receives spiritual intuition.

4 Pretos Velhos are spirits present in Umbanda and Candomblé, Afro-Brazilian religions. They present themselves as old Black men that used to live in senzalas during slavery. They are associated with patience and wisdom.

5 Umbanda is an Afro-Brazilian religion that synthetizes elements from African religion, Indigenous religions, and Christianity.

6 Orixás are deities worshiped by many African beliefs, including Afro-Brazilian religions.

7 Farofa is a traditional Brazilian dish that consists of toasted cassava flour mixed with various ingredients.

8 Cachaça is a Brazilian alcoholic beverage made from sugarcane.

9 Quilombos are communities originally formed by enslaved Black people who were able to escape and resist slavery. With the end of slavery these communities persisted and still do today. People born in a quilombo are called quilombolas.

10 Favelas are a type of Brazilian slum.

11 The Congado is an Afro-Brazilian cultural and religious manifestation. A very old festivity, it is a dramatic dance with singing and music that recreates the coronation of a king of the Congo.

12 The one who is part of the Congado.

13 Grande Otelo, pseudonym of Sebastião Bernardes de Souza Prata, was a Brazilian actor, comedian, singer, producer and composer.

14 Conga is a kind of drum.

15 Maracatu is a traditional Afro-Brazilian musical and performance art form with roots in the northeastern region of Brazil, particularly in the state of Pernambuco. It combines music, dance, theater, and costume, and it holds deep historical and spiritual significance.

16 Part of the Congado.

17 A party for the Orixá, part of Afro-Brazilian religions.

18 Cultural manifestation similar to, or the same as Congado.

19 Atabaque is a kind of drum.

20 Xangô (Shango in English) is an Orixá, a deity in several Afro-Brazilian religions, most notably in Candomblé and Umbanda. He is a powerful and complex figure who holds significant importance in the spiritual and cultural practices of these religions. Xangô is often associated with elements of thunder, justice, and fire.

21 Ogun in English. Ogum is also an Orixá. Associated with iron, war and technology.

22 The Congo king is a Central figure in the Congado.

23 Word play with the word “performance”.

24 Ricardo José Aleixo de Brito is a Brazilian poet, musician, cultural producer, artist and publisher.

25 The crossroads hold significant importance in Afro-Brazilian and broader African diasporic cultures due to their association with spiritual and ritual practices.

26 Samba circles, or rodas de samba, are traditional Brazilian musical gatherings or jam sessions where people come together to play and enjoy samba music.

27 Berimbau is a musical instrument. It is a single-string percussion instrument with a bowl. Originated in Africa, it is commonly used in Brazil, especially in capoeira.

28 In Portuguese: transfluência.

29 Brazilian quilombola thinker.