Davi at the museum

Text by Renata Marquez

Retrato silenciado, paintings by Dalton Paula

The history of art has excluded the aesthetic sensibilities of indigenous people, black people, women, LGBTQ+ and many other communities. It is part of the narratives produced by the distinction between Us and a vast Them, the modern dividing line that separated science and belief, subject and object, art and artifact.

When the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa was in Paris in October 1990, he was taken to visit the old Museum of Mankind on the banks of the Seine River. The visit did not arouse aesthetic enchantment or scientific enlightenment in Davi. Instead, those with him were surprised by a reaction as unexpected as it was evident.

“I was taken to visit a vast house to which the white people gave the name of museum”, says Davi in his book The Falling Sky. “It really made me sad to see all these objects left behind by elders who disappeared in the distant past. But then I saw other glass cases containing the bodies of dead children, their skin hardened and dry. Finally, all this made me very angry. I told myself: ‘Where do these dead come from? Aren’t they ancestors from the beginning of time? Their dried-out skin and bones are a sorry sight! The white people were hostile to them. They killed them with their epidemic fumes and their shotguns to take their land. Then they kept their bodies and now they exhibit them for all to see! What ignorant thought that is!’”

Davi continues his visit astonished, acting as a guide for us. “If the white people want to exhibit their dead, let them smoke-dry their fathers, mothers, wives, and children to show here instead of our forest ancestors! What would they in the city think to see their deceased exhibited like that to strangers?” And at the end, he adds: “We would never do something like that.”

Bruno Latour published We Have Never Been Modern a year after Kopenawa’s account of that unbeatable guided tour through the Museum of Mankind. Latour’s book followed in the footsteps of another anthropologist, Roy Wagner, who drew attention to the fact that, if we are all natives, from a reverse point of view we are all anthropologists.

The former Museum of Mankind no longer exists as such. There was a reopening with a new curatorial proposal in 2015. As the Museum of Mankind, many ethnographic museums around the world have been rethinking their collections and public interfaces. Over the Future of Ethnographic Museums Conference, held at the University of Oxford in July 2013, we even heard that the ethnographic museum was (or should be) dead. If the ethnographic museum appears as the target of a historical series of tragic relationships between the so-called colonizers and the unnamed colonized, the asymmetries of the relationships that violently involve the acts of feeling, seeing, speaking, appearing in public and living together multiply in a frighteningly way.

Us and Them, the great dividing line of our modern experience, is responsible for separating science and belief, human and non-human, subject and object, culture and nature, true and false, legal and illegal. And it is responsible for producing an extensive and strategic set of narratives that seem natural to us once we are not restless enough.

We are in Bamako with the young Brazilian artist Ana Pi. It is 2016, and she guides us to another tour, no less didactic. However, instead of taking us to a museum, we are in a zoo. Ana visits the capital of Mali and, in a video, narrates off-camera: “We are in Africa! Remember those pictures of wild animals? So it is. I did not see it. By the way, I came here to see some wild animals and they brought me to a zoo! It is so funny to think who produces the image of whom… Who produces whose speech? I am in the country where the oldest university knowledge on Planet Earth came from, Mali. Who produces whose body image? The speech? The headline? Who puts it in the newspaper?”.

Strongly inspired by Ana Pi’s questions, it is pedagogical for us to make another visit. We are now in the Accademia Gallery in Florence. In that city, no matter how distracted we try to be, everything leads us to another naked body. Richly portrayed, exhaustively replicated, and collectively revered. This monumental body is also called Davi. Namesake of Kopenawa, the Davi created by Michelangelo is made of marble and measures more than five meters in height. A human monstrosity or a monstrous humanism? Let us remember what Claude Lévi-Strauss once said about anthropology as foundation of democratic humanism: “A democratic humanism that surpasses those that preceded it and were created for the privileged and from privileged civilizations.”

Davi is a born-again descendant of Greek statues, of which historian H. W. Janson wrote in the 1960s: “The female ones we give the general name of Korai (plural of Koré, young woman), the male ones that of Kouroi (plural of Kouros, young man), prudent terms that eliminate the difficulty of a more rigorous identification. We also do not know how to explain why the Kouroi are always naked and the Korai are always dressed”. Gender differentiation as a minor detail. A distinction of genius as a prudent term.

Almost four decades after Janson’s publication, sociologist Richard Sennett wrote another version of Greek history, starting precisely from the point that aroused little or no interest at all to Janson and other historians: slaves, foreign residents, and women had no right to a voice in Pericles’ Athens because they were considered cold bodies – and they were represented always dressed.

In the book Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization, Sennett dedicates a few pages to bring to light a discreet and feminine ritual, not at all monumental, known as Adonia Festival. Once a year, pots of short-lived plants such as lettuce and fennel were grown by women and then left to dry on the roofs of the houses in the blazing sun. Known as Gardens of Adonis, the dried plants used in the ritual celebrated Adonis, eternally young, linked to life, death, and resurrection, therefore to the agricultural calendar, but also to sexual pleasure. The poet Sappho of Lesbos wrote: “Dead sweet Adonis / and now, / Cytherea, / what is left for us? / lacerate the breasts, / maidens, / lacerate the tunics”.

With the narrative of this informal and spontaneous celebration around lettuce, considered by the Greeks a powerful anti-aphrodisiac, Sennett highlights “the denial of the oppressed to suffer passively, as if pain were an unalterable fact of nature”. Here we see the explicit contribution of the micro-history of a sociologist who researched the production contexts of so many anonymous Korai to the narratives of an art historian who was not used to the condition of a symptom of that celebrated male nudity of Davi.

H. W. Janson is one of the eleven authors discussed in Bruno Moreschi’s research, The History of _rt. The artist joined Amalia dos Santos and Gabriel Pereira to produce and analyze data from the dominant bibliographies used in Visual Arts courses in Brazil. In total, 4.405 pages of narratives conventionally accepted as accurate were read and revealed a rather indigestible mass of reading.

Out of a total of 2.443 artists cited in the eleven selected books, 2.402 provided complete data, with a margin of error of 0.34%. The reflection begins with the book covers themselves: the authors of the eleven titles are all white, European or American, nine are men, and only two are women. Looking inside of the books, 2.222 men and 215 women artists are cited (six are without information); of the 2.443 artists mentioned, only 22 are black artists, and only two are women.

While we have access to the statistics that most of the cited artists were born in Italy, United States, France and Germany, a sudden geography of art is drawn before our eyes, omitted by the precedence of an art history. The evidence of this fallacious and ethnocentric geography of art produced a cartography of non-existences: countries without artists, countries without art. Angola, Zambia, Namibia, Saudi Arabia, Nepal, Mongolia, Bolivia or Paraguay do not appear on the map of the arts produced by these books. Conclusion: art historiography has systematically excluded the aesthetic sensibility of indigenous peoples, black people, women, LGBTQ+ and many other communities.

As many sociologists have shown, modern science and law have been the structural pillars of the separation between Us and Them. We have art, and They don’t have art. We have science, and They don’t. But, in fact, who are We? As Westerners and colonized South Americans simultaneously, academics and brand-new colonizers, privileged and marginal within our own cities, we occupy ambiguous positions between Them and Us. And who are They? Has anyone, by any chance, heard of Them as women?

In fact in the volume dedicated to the Renaissance, Janson says nothing about Artemisia Gentileschi, the first woman accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, the same school that Michelangelo had gone through decades before. And the worst thing is that we don’t even notice this absence, so natural that art history seems to us to be. Artemisia was born in Rome 29 years after Michelangelo’s death. She painted both Biblical and not-so-Biblical Susanas and Judiths since she had been the victim of rape in her home.

Nor do we notice the lack of Plautilla Nelli, a painter praised by the scholar Vasari in the 16th century, who had an exhibition in 2017 at Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is surprising for our era to realize that Pliny, Bocaccio, and Vasari, respectively, in the 1st, 14th, and 16th centuries, manage to mention more women artists in their writings than our contemporary Janson. Our advantage seems to be that, as you may have noticed, we wander around looking for historiographies in places other than just the main bibliographies.

We are now at Slam das Minas, in São Paulo, where Luz Ribeiro sings her poem Menimelimeters. “When ya mention broken in your dissertations and theses / do ya mention the color of the walls as natural clay brick? / do ya mention the six children who sleep together? / do ya mention the ice cream that is good just because it costs 1.00? / do ya mention that when you arrive to do your research your windows don’t go down? / ya don’t quote, ya don’t listen / ya just talk, fallacy!”

We have at our disposal billions of pages or, in the case of Moreschi’s research, eleven books composed of what Michel de Certeau called “the conquering writing”. The author of The Writing of History and The Invention of Daily Life discusses history as historiography, that is: as writing, mainly because of its “aspect of fabrication and no longer of reading or interpretation”. Thus, a double problem is pointed out, a political and subjective problem. Who writes the history? For what or for whom? How do they do it?

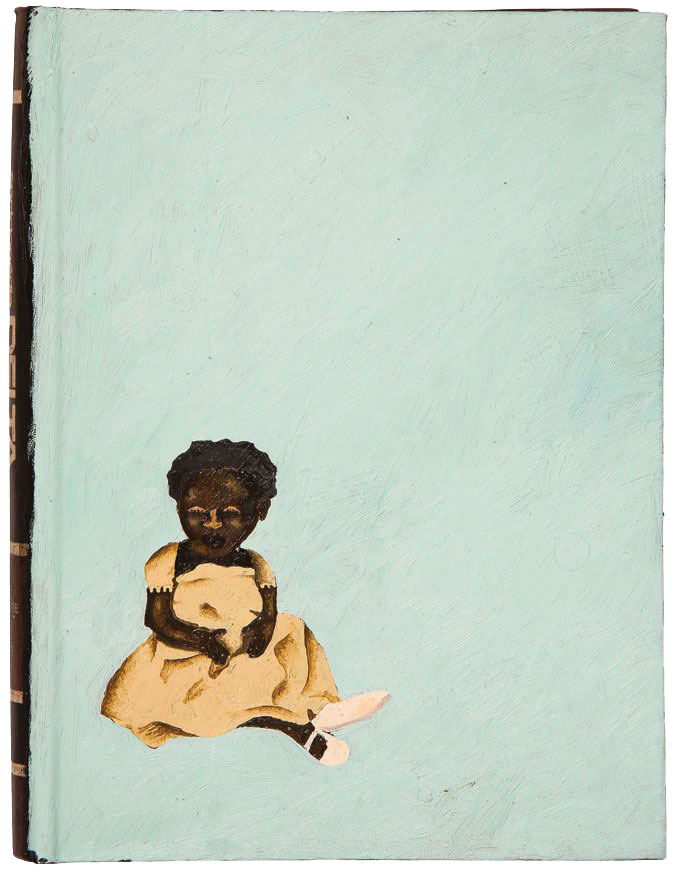

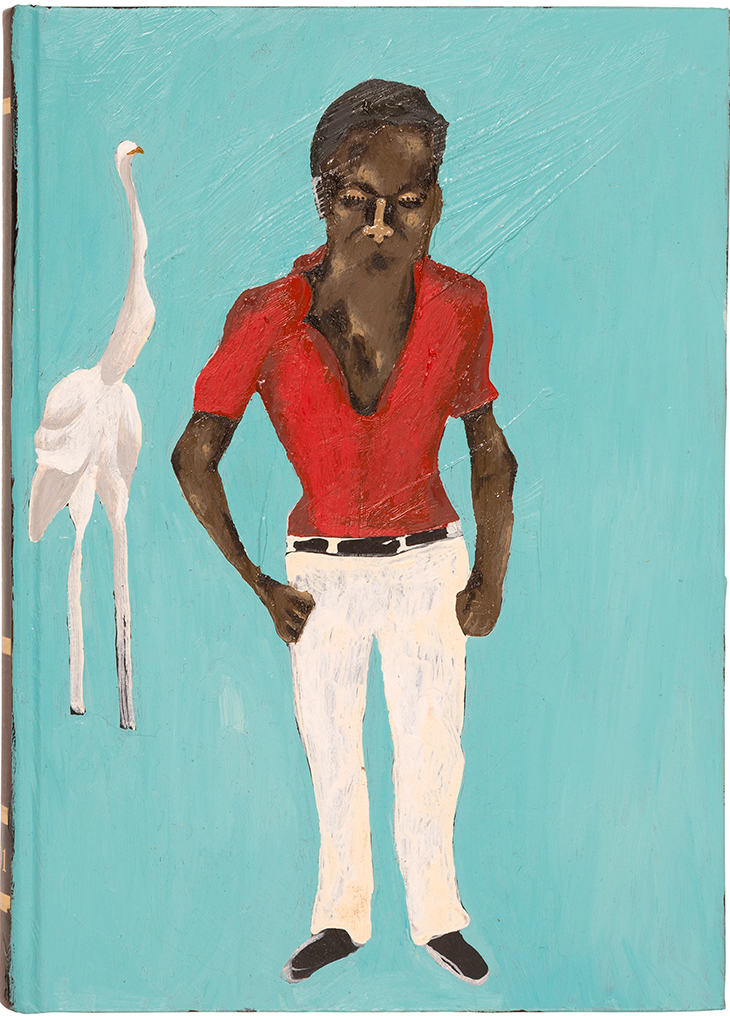

Let’s make a brief stop to see Mestizo Histories exhibition in São Paulo, where, in 2014, artist Dalton Paula exhibited Silenced Portrait. In this installation, comprising 19 volumes of Barsa Encyclopedia, Dalton covered the traditional encyclopedias with paintings of black women. The act of occupying the covers with new characters makes encyclopedism immediately obsolete. But who are these unknown women? We soon learn that they are fictional women. Derived from real women, he displaced them from the popular photopaintings found in religious ex-voto rooms and in domestic interiors throughout Brazil. Dalton says that he traveled with his companion through the hinterland of Cariri in Ceara, Brazil. They traveled more than 5,000km between Goiás, Minas Gerais, Bahia and Ceara collecting images of private environments and pilgrimage routes.

The artist was particularly interested in the pictorial and temporal retouching the popular photopaintings can make. “The possibilities that this artistic form has reached are surprising, the complex uses and meanings that it contemplates, as in the cases of deceased people who ‘come back to life’ when they portrayed them with their eyes open, or elderly widows who keep only images of their husbands when they were young – the painted portrait unites these two images and temporalities, that is, a lady over sixty years old and a twenty-year-old young man seem, thus, to be mother and son or even grandmother and grandson. Photopainting also allows a poor person to appear in elegant clothes, which he would not normally be able to afford. Thus, I create for each character, and everything he/she brings with him/her, a story of protagonism and authorship, reworked on the covers of these universal publication”.

Leaving Instituto Tomie Othake, where we left Silenced Portrait, we can walk a little along Brigadeiro Faria Lima Avenue. The São Paulas project, developed in 2016 by Medida SP in partnership with Leila Santiago, merges data from Geosampa and IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) and makes us contemplate the far from banal street names. According to the survey, around 5.000 public places in the city are named after women. Out of almost 70.000 public places, nearly 27.500 have masculine names. As if that were not enough, the sum of kilometers of public spaces for men is at least six times greater than those with female denominations. The most common title for female names is “saint,” while for masculine names it is “doctor.” If avenues or alleys is also a determining factor of the gender of toponyms.

In 1989, Guerrilla Girls collective asked, “Do women have to be naked to enter the Metropolitan Museum?”. The same question was addressed to MASP by them in 2017: “Do women need to be naked to enter São Paulo Museum of Art?”. Undoubtedly it is a great question, capable of preserving all your intelligence and joviality at almost 30 years old. But the question asked by the Guerrilla Girls reminds us, at the very least, of another equivalent question. Why have there been no great women artists? It is the title of an essay published in 1971 by Linda Nochlin, a historian who died in October 2017. Did anyone out there read it? The text, which was originally published by ArtNews magazine, was only translated into Portuguese in 2016 at the initiative of the independent Aurora Editors in São Paulo.

As Nochlin demonstrated, the question requires a closer analysis. “First we must ask ourselves who is formulating these ‘questions’, and then, what purposes such formulations may serve”. Above all, according to the author, we must ask ourselves about the productive conditions of a “genial art”. “What if Picasso had been born a girl? Would Senor Ruiz have paid as much attention or stimulated as much ambition of achievement in a little Pablita?” Art history is thus revealed to be based on “romantic, elitist, individual-glorifying, and monograph-producing substructure”, articulated with “specific and definable social institutions, be they art academies, systems of patronage, mythologies of the divine creator, artist as he-man or social outcast”, says Nochlin.

“The conquering writing”, however, is not done only by words, phrases, and books. Another survey, carried out in 2014 by the Group of Multidisciplinary Studies of Affirmative Action at UERJ (Rio de Janeiro State University, Brazil), analyzed the 20 films with the highest national box office between 2002 and 2014 and found that, on average, 45% of the main cast were white men and 35% were white women, while the percentage of black men was 15% and black women 5%. If only rarely did any of these films feature a black woman, they also found there were no black female directors or screenwriters. White men make up 84% of directors and 69% of screenwriters. White women are 24% of screenwriters and 14% of directors, while black men are only 3% of screenwriters and 2% of directors.

Statistics, that suspicious element accused of dehumanizing sociology and translating social relations into economic language, seem to assume a redemptive role in the historiography of the art critique. Statistics are evidence against the place of power of those who choose what is to be seen as well as what is not to be noticed. In the field of the most important international art exhibitions, Kassel Documenta, which takes place every five years in Germany since 1955, only in 1997 had a woman at the head of Documenta X for the first time, Catherine David. Ten years later, a percentage was the protagonist of the curatorship of Documenta XII: for the first time, the show featured 50% of female artists. Previously, in 1999, numbers also constituted the flag of the Venice Biennale, whose curator had established that at least 30% of invited artists should be women.

“Because it matches.” That was the quick answer Lira Huni Kuin gave me when I asked, looking at the beaded bracelets she made and curious about the black lines that outlined its graphics. Lira is the daughter of Maria Huni Kuin and Joaquim Maná, indigenous people of Huni Kuin ethnic group from Acre, Brazil, or Kaxinawá people, as we usually, on the rare occasions we have, call them. Joaquim is a teacher and has researched kene, traditional graphics that structure Huni Kuin life present in body painting, cotton weaving, and, more recently, in bead adornments.

About 30 years ago, Maria learned the art of kene from Helena, a lady from the Purus River region, one of the few ancient Huni Kuin women who retained the knowledge of kene. He learned weaving, spinning cotton from the fields, dyeing the threads with saffron or tree bark, and weaving hammocks and clothes. She says that the complex kene, today displaced to the beaded objects I admired while we talked, were originally written on fabrics.

“Txere beru for us is like the letter A for white people. It is the beginning of everything in kene”, says Huni Kuin shaman in Kene Yuxi, a film made in 2010 by the son of Maria and Joaquim, Zezinho Yube, who continues his father’s research. Txere beru is the design of the eye of a curica, a type of parrot, which is the first design that girls learn to do and then try the more elaborate graphics. But there is an important detail in kene pedagogy. The older women, who knew how to spin cotton from the old fields and know the art of drawing the kene, no longer have the sharp eyes to work with the tiny and challenging beads, which is left to the young women who no longer want to spin or dye cotton threads.

Tired eyesight arrives out of sync with the preoccupied mirage of memory. In the transit of kene drawings that go from a traditional support to a foreign another, a powerful frontier is perceived in which both can continually change places. In this transit new alliances can happen as well – alliances between generations of kene women and alliances with non-indigenous men and women.

Arriving at the exhibition On the Path of Beads, organized by anthropologist Els Lagrou at Indian Museum, in Rio de Janeiro in 2015, we enter a requalified aesthetic world in which those dichotomies of modernity lose their meaning. Art and artifact, ritual and daily life, abstract and figurative follow the same movement of permutation undertaken by the terms traditional and foreign. Lira, Maria, and dozens of other indigenous artists showed their works at the Indian Museum. During the invasion of America, beads were already a key element of seduction and negotiation. Glass beads are experienced here not as an end but as pure circularity. From a colonial trinket to a work of art that “pacifies white people”, as Lagrou wrote.

It is an ethnographic museology proposal diametrically opposed to the one that Davi Kopenawa had contemplated in horror, it is true, but let us remember that we are still in the Indian Museum, and the fact that I can appreciate and distinguish a Kaxinawá from a Krahô or Juruna drawing, without being an anthropologist and having studied Visual Arts, is beyond doubt not the merit of my graduate academic training.

A new indigenous female protagonism is what the beads also tell us. We are here, and They boldly come to meet us in the city. They have always reserved a prominent place in their cosmology for Us, the Others. Women who master traditional practices and thus become travelers, diplomats between worlds. Their aesthetic flag of pacification of the white people is a multicolored, tactile flag that can be incorporated (also by us), with endless versions of drawings learned from the parrot, the snake or the armadillo, according to the stories of ancient times.

However, we continue to be haunted by Ana Pi’s question: “Who puts it in the newspaper?”. Professor José Ribamar Bessa Freire was bothered by the invisibility given to Labrou’s exhibition: “I read articles about Google announcement in Brazil that opens the Youtube headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, about the gastronomy championship, about Dee Bufato, who plays with Sean Diss at Arte Inn, about the Somm and Gop Tun collectives, which run Countdown at Mira, about the song Nhenhenhen and Maísa’s ten-year career on television and about Ana Maria Braga’s new cookbook. All topics of transcendental importance, of course. Nothing about the beads.”

A world without art. This is what we bequeathed to our indigenous friends, excluded from an official historiography that inscribes visibilities and non-existences. The answer Lira gave me during that conversation was devastating. “Because it matches” is an answer we wouldn’t be able to give in a classroom, although it’s probably what we’d often like to say. “Because it matches” is the perfect answer to an imperfect question. Were we expecting a metaphysical answer? A philosophical answer? A logical answer? Or an exotic answer? That’s right, there isn’t one. Instead, what we got was a genuinely aesthetic response.

Indeed, we are not talking about a kind of aesthetic subjectivism which, after all, is the face immediately equivalent to scientific objectivism, that is: both endogenous, elitist, and exclusive fields. Preferably, we are talking about a genuine aesthetic life and a shared gaze between Huni Kuin women and Us.

In this sense, I understand that there are two aesthetic movements underway today. The first is a movement of inclusion, albeit late, of everything that has existed without existing; and the second movement is one of revision – of what we are, of what we could be. These two movements are not mutually exclusive, of course. Nor are they hierarchically dependent, but rather juxtaposed.

Through historical guilt, we have opened courses, written chapters, and opened exhibitions for inclusion. If the problem seems to lie in the concepts we have constructed, which are extremely limited and have signs of running out of steam, through this insufficiency or disgust with the concepts we have, we train our ears for new learning.

Alongside the actions of including in art what we used to recognize as artifacts, undoubtedly a counter-colonial path of a contemporary anthropology of the arts, a truly revolutionary act seems to me to be able to be, one day, capable of no longer seeing art in our exhausted history of art, but to experience it in its extra-field and with its power to think, explain and act on the world, as Davi Kopenawa and Lira Huni Kuin generously teach us.

Renata Marquez is one of the editors of PISEAGRAMA magazine.

Dalton Paula is a visual artist who had participated in Mestizo Histories Exhibition, in 2ª Chongquing Biennal and 32ª São Paulo Biennal, among others exhibitions in Brazil and abroad. He lives and works in Goiânia, Brazil.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in PISEAGRAMA 11, in November 2017.

The translation into English had the collaboration of Adriana Galuppo.

How to quote

MARQUEZ, Renata. Davi at the Museum. PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, March 2024.