Guarani vegetable language

Text by Izaque João

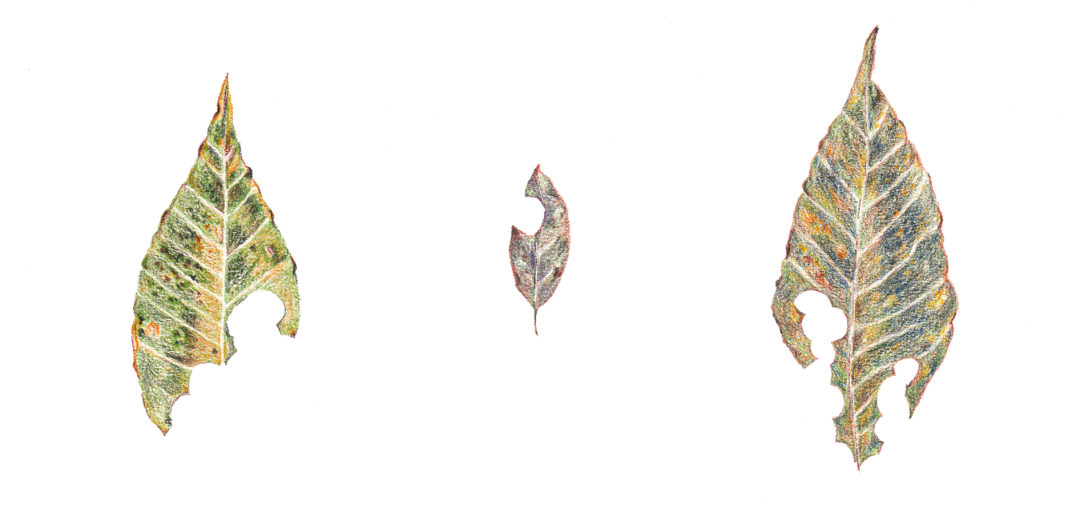

Palavras mordidas, drawings of conversations with saúva ants by Ana Flávia Marú

For us, Kaiowá, plants are not merely resources. Each has its own function in the terrestrial world, which goes beyond its usefulness to humans. In addition to being part of terrestrial life, they bring us knowledge and collaborate in balancing the socio-cosmological space. If the idea of domestication in non-Indigenous societies is linked to progress, evolution, control, and subjugation, in Kaiowá thinking we understand that it is urgent to eradicate the idea of the submission of plants.

To understand what an animal or plant is within the Kaiowá(1) thinking one needs to know our origin story, ypy,(2) which tells us how everything came to be. All things have a divine origin. Every existing thing – humans, birds, animals, plants, objects – was created by the deities at Áry Ypy, the space-time of origin, and belongs to them. The mythical narratives disclose the creation process and define the rules, habits, and behaviors that must be followed, as well as the political strategies for relating to the gods, which all are expressed in songs-prayers-dances. Such rules are fundamental for our interaction and reciprocity with the divine world. Thus, the earth space occupied by the Kaiowá is understood as a social-political space, depending on prayer for its balance.

It was through the singing of the divine creator that the essences of animals and plants, what we call rekorã ypy, or life’s distinctive principle, came to be. When everything originated, the creator defined for each being its living space, its behavior and function on Earth, its language, food, way of walking, etc. All actions and social norms were established in this primordial time-space.

Deities, spirits, humans, animals, and plants reside in different environments and have specific behaviors and ways of living. The hawk, for example, is a carnivorous bird. In Kaiowá thinking, it was established from the beginning that its food would be the meat of other animals. Other birds feed on insects or fruit, and this type of behavior was also established in their rekorã ypy. The same applies to vegetables: at the time of their creation, their cycles and the seasons in which they bear fruit and flourish were conceived.

During the cosmos’ initial constitution, each space was specifically put aside for each species, according to its condition and function. Each environment is then considered to belong to a particular type of being, that is, as an originally intended space. If there are living spaces shared by several beings, there are also territories that were specially designated for each of those beings. It is possible to cross and move through these spaces without appropriating them. We Kaiowá know that each animal and each plant has its environment, as well as its way of acting, eating, moving, and communicating.

To lodge and accommodate plants in a suitable environment one should be in dialogue with yvyresapa, Earth’s primordial foundation, which promotes and maintains plant diversity. In the subterranean world, plants intertwine with each other, through their roots, as a form of cooperation and to maintain balance for collective coexistence.

In the beginning, all beings had human form. There was, however, a critical and crucial point in which plants and animals were endowed with “clothes” that hid their original characteristics. In Kaiowá cosmology, beings inhabit two planes: the terrestrial plane, located on Earth; and the divine plane, located in the beyond, called yvy rendy, the divine level. The ñanderu, our prayers, explain that, in yvy rendy, all beings walk and are immortal. The original molds of plants and sacred beings are found in yvy rendy, which is not the Earth we are treading on, but an Earth that is beyond our imagination and that our eyes cannot see.

The ñanderu tell us that whatever we see with our eyes on this terrestrial plane as a plant, or a tree, or an animal, actually has a human form in the yvy rendy. If we went there, to the other side of the world, beyond the Earth, to yvy rendy, we would see the trees that we see here as people. We would see them walking, but their gait is not the same as that of animals or humans. The vegetable gait is considered the most beautiful.

In his theory of Amerindian perspectivism, anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro explains that “the way human beings see animals and other subjectivities that inhabit the universe — gods, spirits, the dead, inhabitants of other cosmic levels, plants, meteorological phenomena, landforms, objects, and artifacts— is profoundly different from the way these beings see humans and themselves.” According to this theory, animals and other beings could be considered former humans.

However, animals and plants are not former humans. In the Kaiowá cosmovision, those beings still have humane characteristics on the plane they inhabit, and so forth. What makes plants and animals different from humans was established at the beginning of life. We call it ohekokuaa, each being’s wisdom about how to live, how to produce knowledge, how to behave, and how to communicate. It is different from what biology classifies as “species”. For the Kaiowá people, what defines and differentiates beings is their ohekokuaa, defined at the Áry ypy.

The ohekokuaa is the bond that connects each life to its knowledge;, it is what defines ways of being and behaviors, how a being relates to others, where they live, and where they belong. The ohekokuaa is a divine precept that articulates two origin strokes: heko, which means life or to give life, referring also to developing and growing, and kuaa, a suffix that indicates a set of knowledge. The emergence of plants, animals, and other beings was not instant, it happened in phases until they were fully constituted.

At the moment of creation, the tekoaruvicha, or deities, gathered and made the plants – as well as all other beings – emerge through chanting. The words expressed through these songs constituted all that exists. Ñanderuvusu was the one who, through songs, defined the essence of plants and demarcated their knowledge within their vegetal condition. The ohekokuaa thus prescribed the functions of plants in the social space, including their mode of interaction with humans and non-human beings. The deities began to walk around the world, and where they passed, they sang; thus, different plants were born and grew, forming large forests.

Plants are special beings, since the beginning of time. On the Earth’s surface, they influence all other beings, and they also interact with the beings that inhabit the underworld. Plants need earth in order to be born, grow and firm their roots. If biology understands that for the development of plants they need good soil, in our way of thinking there are other things to be considered.

Lício Toriba, a prayer who has passed away and with whom I used to talk a lot, explained to me what the roots of plants are. The roots scatter underneath the ground, where they meet other roots. The plants are not isolated or alone; otherwise, they would be sad. When the roots interweave, they strengthen each other. Lício told me we are the same. When we are alone, we become sad, but when we have other people to talk to and exchange with, we can live happy lives. The roots are underground so that plants can communicate among themselves – that is their omohekorã. That is “how they were created”.

Leaves also have their specificities. They fall and make noises. Seemingly it is an insignificant thing to see a leaf fall and make a sound. However, that is also a soft form of communication. Foliar balance is in the Jerosy Puku ritual, the Great Chant. The movement of the leaves is not just movement, it is also a form of dancing. Tree branches rub against each other producing sounds that are sometimes warnings. All these things that are said by plants and trees, that we can hear but not understand, are the yvyra ayvu, the language of trees. Or ka’aguy ayvu, the language of the forest.

Plants considered sacred – such as achiote (yruku), musk (ysy) or cedar (jurakatĩngy) – influence native spirits at different cosmic levels, who interact during the rituals with both human and non-human beings and collaborate in maintaining social order. The use of these sacred plants also helps our physical, mental, and spiritual consolidation.

These sacred plants belong to their own territory, which we call yvyra jekokatu rekuaty. Their use in medicinal or spiritual therapies requires deep knowledge. In Kaiowá thinking, correct handling and use are essential to obtain the desired results. To use achiote, cedar, or musk in ritual ceremonies requires special procedures, preparations, and care.

Plants have their way of communicating, which is different from ours. In the forest, we can hear them. Trees can indicate danger through noise. When I was a child, I would go to the forest with my father; he could understand when trees talked. He would explain to me that going under some trees can be dangerous, depending on the noise and movement they are making. The trees themselves warn us. They make noises, like whistles, which the Kaiowá identify. We know perfectly well when they are warning us to move.

The achiote tree has a primordial song – called yruku arekory – which enables harmonic reciprocity among plants and humans. If that song is not sung correctly, there will be consequences, and some form of social imbalance of variable severity may occur. The achiote has the power to transform the environment, and therefore we must be in constant dialogue with it, which we do through chanting.

I have an achiote at home and I know that sometimes I need to prune its branches. Since it is not merely a tree, I cannot just prune it and be done with it. First, I need to talk to it and then I can prune it slowly and carefully. The achiote is a sacred plant, and while it is here on Earth, it is also on the other world, in yvy rendy. Therefore, the pruning must be done carefully. It took me a while to understand this kind of care for plants, which I learned from the prayers and the elders.

Within Kaiowá thinking, each plant has an appropriate way to be cultivated. Some are planted by spirits, and they seem to grow naturally; others are planted by us, humans, and some are cultivated by birds – it depends on their cosmic situation. Our crop techniques were also determined in the Áry Ypy. The edible plants, itymbýry, farmed by the Kaiowá need constant care. They need to be taken care of for their well-being and development. Each plant growth cycle is called ypyky: ypy indicates their origin or principle, and ky is the sprouting.

Even though the world is now facing climate changes, Kaiowá traditional family agriculture is still guided by the phases of the moon, the rainy season, the singing of birds and cicadas, the flowering of the ipê(3) tree and the changing position of the sun. The songs of the birds guide us; they work as a calendar. By recognizing them we know the season of the year, if it is planting period, if the cold of the winter is over, if it is a fecund moment with many fish in the river, or if the wind is going to be strong. Some can even recognize the arrival of storms by the singing of birds.

Each phase of plant growth must be looked after very carefully. The itymbýry are delicate, and special attention must be paid to their flowering phase and the ripening period. Otherwise, these foods can develop anomalies and, when consumed, cause social or individual imbalance. In order to feed ourselves safely and healthily, vegetables must be ritualized, itymbýry ohovasa, through the Jerosy Puku ceremony. In the Kaiowá worldview, there is a hierarchy principle applied to all agricultural products, in which the saboró(4) corn (jakaira) is considered the foremost and most delicate.

Agricultural products need to go through the process of jehovasa, or blessing, in order to develop properly and become food. The term jehovasa has multiple meanings. I could simplify by saying that it is a gesture made with the hands, first forward, then to the right, and then to the left, which has an important meaning in our spiritual life. According to prayer Luiz Anguja, from the Panambizinho Indigenous Territory,(5) it represents the journey in search of high celestial levels and works for communicating with the deities.

If the jehovasa is not done, plants will no longer reproduce, they will no longer exist on Earth. It would be as if the deities collected these specimens and took them back to the yvy rendy, because without jehovasa they cannot live in the earthly space. However, I must clarify that for the Kaiowá the idea of extinction does not make sense. For us, what happens is the collection, the removal of the specimen from Earth. In the region where I live today, many plants do not exist anymore. The same thing is happening with fish. When the rivers are very polluted, if pesticides are being thrown into the water all the time, the fish also disappear, that is, they are collected. It is not an extinction. It’s a pick up.

When plants cease to exist in the earthly world, knowledge about them also disappears. If I talk to children and young people about a plant that I knew and it no longer exists, they will never have the opportunity to understand it, much less to know its stories. Along with the removal of beings, knowledge is also removed.

There is, however, the possibility of bringing collected beings back. About ten years ago, when I was participating in an Aty Guasu, or large assembly, I heard the ñanderu talking. Today, unfortunately, they are all deceased. They were remarking that there is a way to bring things back, which is done through a song called omopyrũ (“I will bring it back”). That song can bring back “extinct” plants, birds, or fish.

It is only possible to bring them back, however, as long as there is water that is not polluted; as long as there is a forest and that there are fruits and food that they can consume. There must be an adequate environment for them. Each place has its specificities, that is to say, there is a specific place for animals, birds, fish, and plants. The omopyrũ functions as a negotiation, as a dialogue with the guardians of beings. The guardians are those who allow the return; they are responsible for returning their creation to the earthly plane. In the case of sacred materials – such as mimby, the sacred flute, mbaraka, the rattle, and many others – once collected they can no longer come back because their original territory is not on Earth, it is in the beyond, up there. Here, they are only on loan.

This collecting also affects people’s behavior. For us Kaiowá, all abnormal things need to be balanced, they need to be controlled, and for that, there must be a person who knows and can establish a dialogue. Not everyone has this ability. If someone asks me, “Izaque, could you sing to stop such a thing?”, or “Izaque, could you bring back such a species?”, I would not be able to do it. The ñanderu are the ones that have this knowledge, they are the prayers, who acquired such wisdom throughout life.

For us, Kaiowá, plants are not merely resources. Each has its own function in the terrestrial world, which goes beyond its usefulness to humans. In addition to being part of terrestrial life, they bring us knowledge and collaborate in balancing the socio-cosmological space. If the idea of domestication in non-Indigenous societies is linked to progress, evolution, control, and subjugation, in Kaiowá thinking we understand that it is urgent to eradicate the idea of the submission of plants. It has to be emphasized that they bring us knowledge anchored in the precepts of existence.

We understand the shape of a forest as the result of the combined actions of animals, humans, and non-human beings; visible beings and non-visible beings that lead to vegetal diversity: edible plants, fruit trees, sacred plants, and medicinal plants, among others. Forests also house different species; they are a home for many. Thus, reforestation is a way of giving continuity to existence and maintaining diversity.

Kaiowá narratives demonstrate that our ordinary human eyes are blind to the peculiar way of living of plants and that we are deaf to their language – that is, we cannot see them in their original form or understand what they say. Our way of communicating is in absolute disharmony with plants, not only because we lack understanding, but also because the language of plants is perfect. Words uttered by plants are perfection.

Atanásio Teixeira, a very important prayer for the Kaiowá people, who currently lives in the Aldeia Limão Verde Indigenous Territory, told me that at the beginning of times human ears were covered with seven layers of sacred cotton, mandiju ete, which is what still prevents us from hearing and understanding the languages of other beings, different from us. This happened so we wouldn’t be able to hear the conversations among deities that took place on the other side of the world; we can only hear things on this side. The same goes for our eyes. Atanásio explained that our eyes are covered in layers that prevent us from seeing other beings in their original form. We see a bird just like a bird, with feathers and beaks. However, in reality that bird is a person in its original, authentic form.

Ordinary eyes can sometimes even see, but they do not understand what they see. For example, sometimes we see lightning in the sky. The lightning, in reality, is not just lightning, they are a form of dialogue, an exchange of experiences between the deities or between non-human beings. It is the same with birds. We listen to them without knowing that many times they are communicating with each other. Sometimes birds are singing their guahu, a kind of song-prayer-dance; other times, they are speaking to us, in order to alert us about bad situations. Every guahu has its own story, and every being speaks through its guahu, telling through songs how they lived at the beginning.

Birds are also our companions. The late prayer Paulito Aquino, who lived in the Panambizinho Indigenous Territory, once told me the story of how a tinamus bird, which we know as ja’o, warned him and his mother of danger in the forest, indicating the right path for them to follow. The language of birds exists in different forms, but our ears often fail to understand their guyra ayvu or the language of birds. Communication can be carried out in other ways, not only through singing but also through non-verbal communication, such as through their behavior and reactions, just as in the movement of trees which indicated the correct path to Paulito.

To be able to understand and dialogue with plants and other non-human beings it is necessary to have a special spiritual, body, and mind preparation. Not everyone can achieve this preparation, as it requires full, exclusive dedication. For this reason, many people abandon spiritual preparation and analyze plants and animals from a conception that is inappropriate, just because it is easier. Shamans are the only people who have the skills to take on the role of active interlocutors of plants and other non-human beings, being able to listen and understand the voices of different beings and converse with them. In this sense, any other individual is a layman, because they do not have the shaman’s abilities to transit through different cosmic levels.

The ñanderu and ñandesy, male and female prayers, go through spiritual preparation throughout their lives to learn. As Atanásio says in the book Cantos dos Animais Primordiais,(6) which I recently edited, “It takes many stages of learning to understand each space or to know the many ancient knowledges; just like in school, to acquire profound knowledge we have to attend classes every day. Only then will we be able to understand those who talk about life in its entireness”. This is how, over time, the layers that cover their eyes and ears are removed and they manage not only to see and hear the original forms of beings, but to understand and memorize them in order to communicate. If all people had access to this kind of knowledge, they would understand that plants are not just plants.

It is on this path of knowledge and Indigenous shamanism that the sciences should be anchored to better understand the importance and diversity of plants and animals. When non-Indigenous people finally understand the functions and ways of life of plants on Earth, established in primordial times, it will be much easier to take care of them, protect them, respect their territory, and live together with them harmoniously.

In Indigenous schools, we try to teach our own values and traditional knowledge. Several teachers work with their students in the classroom and outside the school building, near streams, rivers, and in the woods. This is essential so that children and young people get to know the importance of plants up close.

Indigenous philosophy and science, contrary to what many people think, are neither fantastical nor just empirical. Western science often has an opposite interpretation of Indigenous science, delegitimizing it. The word myth does not even exist in the Kaiowá language; for us, the knowledge that originates from the time-space narratives of origin is our philosophy, and cannot be reduced to imagination. Fortunately, some studies do take the millenary knowledge of Indigenous peoples as a starting point and show that we interact reciprocally with the diversity of beings, building harmony and coexisting together.

What would happen if we cut down all the trees? If Brazil turned into a desert – what would life be like? What would the air we breathe be like? How would we live our daily lives? Now there are fewer and fewer trees. There are practically only monoculture farms around our villages. The cosmic environment has its own organization; each being occupies a specific space and fulfills a particular function, as established in its origin. The forest and the woods are the appropriate places for the production and reproduction of these species, be they plants, animals, or spiritual beings. In turn, each being has a very important role in the construction and ongoing maintenance of forests and woods. The ñanderu insist on reminding us that we humans do not live alone; we are not isolated, and we need each other. Non-Indigenous society and science need to understand the space that plants occupy on Earth and what their function is, because only then will they be able to take care of them, respect their territory and relate to them in order to live in harmony.

–

Izaque João belongs to Brazilian Kaiowá Indigenous group. He is a teacher, holds a master’s degree in History from the Universidade Federal de Grande Dourados and is a doctoral candidate in Anthropology at Universidade de Sāo Paulo. He taught at the Joãozinho Carapé Fernando Indigenous School in the Panambi indigenous community in Mato Grosso do Sul.

Ana Flávia Marú is an artist and architect born in Itumbiara, Goiás. She is a member of Natural History of Goyaz group, a master’s student at UFG and a collaborating artist with the independent space Muquifu Cultural in Goiânia.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in the book Terra: antogia afro-indígena (PISEAGRAMA + UBU, 2023) and translated into English by Brena O’Dwyer.

How to quote

JOÃO, Izaque. Guarani Vegetable Language. PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, December 2023.

Notes

1 Also known as Guarani-Kaiowá. Guarani is a group of culturally-related indigenous peoples of South America. The Kaiowá are one of three Guarani sub-groups. In Brazil, they live in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Guarani is also the language spoken by these peoples.

2 All the words in italics are Guarani words (the original text was written in Portuguese with the Guarani words in italics).

3 The ipê tree is a genus of plants very common in South America, its scientific name is “Handroanthus” and the most common English translation is “ipe”, I decided to leave this word in Portuguese as it is not a common tree outside South America.

4 Saboró is a type of white corn.

5 Indigenous Territories are areas inhabited and owned by Indigenous peoples as recognized by the Brazilian Constitution. Panambizinho is located in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

6 Published by Hedra Editoria. The title translates to “The songs of primordial animals”.