Listening-writings (and vice versa)

Text by PISEAGRAMA

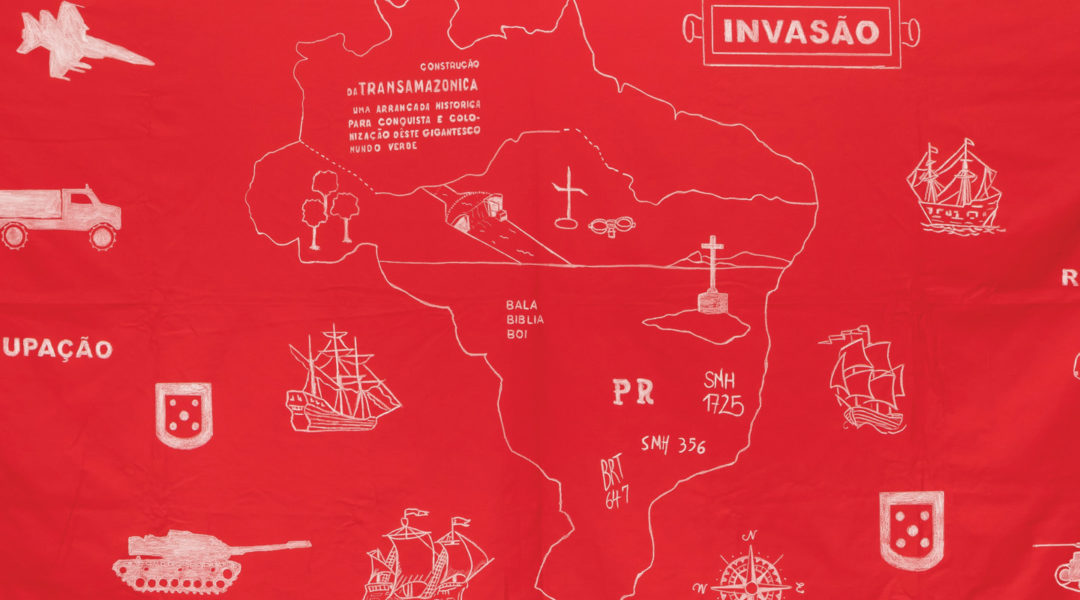

Invasão, drawing by Jaime Lauriano

How can we meet the urgent and generous thoughts and messages by the people who live on the earth? Thoughts and messages addressed to the juruá, the napë, the cupen, the tihi, the whites, the colonialists, the city-dwellers, by the people who, from their territories, realize life differently? How do we reshape our gaze, our listening, our writing, our reading and our actions, in the face of the practices and thoughts of communities that have survived various forms of violence daily – for 523 years? How to trace a reconnection to the land in the company of those who have never been separated from it?

Terra: Afro-Indigenous Anthology brings together essays published in Piseagrama magazine over 13 years and also some unpublished essays, all authored by Afro and/or Indigenous writers. Each of them holds a unique story of encounters, listenings, and shared writings; each piece of writing is rooted in endless conversations and harbors alliances that are not made without conflicts or misunderstandings. Somewhere between orality and writing, we have constructed an editorial method through the publication of printed oralities.

The conversations that gave rise to Terra took place in public gatherings such as festivals, classes, lectures, panel discussions, and academic forums; in concentrated work sessions centered in writing; in the collection of scattered speeches and hidden broadcasting sessions; in carefully reading and editing theses and dissertations; in remote video conference meetings; in endless WhatsApp audio exchanges and lengthy telephone readings. These are encounters that initiated dialogues, friendships, and interactions which paved the way for the sharing of knowledge, and fertilized alliances beyond the editorial boundaries of the texts produced.

Each essay tells the story of an encounter, and each encounter connects us with the author’s territory of origin. The Afro-Indigenous Anthology thus assembled is also a cartographic writing of the Afro-Pindorama land, a surge of knowledge, memories, bodies and struggles that inhabit many parts of the country. In this other map of Brazil, with its many lands and territories, languages and expressions, bodies and corporealities, our writing as editors is a form of listening-writing (and vice versa). Listened-to writings challenge the canonic form, defy academic productivity, and enable words crucial for the maintenance of life spaces to be transported, distributed, and shared. With such printed oralities, we also set in motion a bibliographic occupation tactic: the systematic publication of texts generated through listening-writing as an intrusion into the bibliographies of university courses, theses, and dissertations; into the pluriverses of the Metaverse; and into the writings of Western authors who can thus engage with the orality of traditional knowledge.

Our writing, in the capacity of editors and publishers, is also a form of care. Writing and editing merge into a possible way of caring for what needs to be urgently passed on, and of preserving and safeguarding worlds. This book is, therefore, a partner in the struggles — for the reclamation of territories, for differentiated education, for food sovereignty, for everyday nature-cultures, for traditional medicine, for forests to be standing, for the decolonization of architecture, for the denormatization of bodies, for the reforestation of cities, for the indigenization of politics, and so many others.

In 1980, the Oglala Sioux indian Waŋblí Ohítika, also known as Russell Means, said that “It seems that the only way to communicate with the white man’s world is through the dead, dry pages of a book”. “They have already made known through their history that they are incapable of listening and seeing; they can only read”. According to him, writing “sums up the European concept of ‘legitimate’ thought; what is written has an importance denied to what is spoken”. By “imposing an abstraction on the relationships that are established in speech”, books would be “one of the means by which the white man destroys the cultures of non-European peoples”.

The political process of “demarcating space in writing”, talked about by anthropologist and educator Braulina Baniwa, raises a series of questions and destabilizes the place of ease and privilege legitimized by the alleged universality of writing. In 2016, in the Mekukradjá Circle of Knowledge, writer Daniel Munduruku stated that “what we do when writing our texts is not a denial of orality but an update of orality itself, because we understand that our children and grandchildren will be able to reconstruct stories and rebuild orality by mastering writing”. Ailton Krenak adds that beyond the unresolvable opposition between orality and writing, what truly matters is being “the bearer of a narrative, of a worldview that can empower and strengthen the place of existence of one’s community, one’s collective and, in our case, of our peoples”.

Writer Conceição Evaristo recalls that “perhaps the first graphic symbol presented to me as writing came from an old gesture made by my mother”. She invokes the memory of her mother crouched on the ground, drawing the sun with a twig in an attempt to call on it during rainy days. “It was a ritual of writing made up of multiple gestures, in which not only her fingers moved, but her entire body too. And also our bodies moved in space, following our mother’s steps toward the earth-page where the sun would be written.” In her effort to record her writing in a multiple ancestral gesture that transcends paper, Conceição Evaristo teaches us that the ground can also be a page; something that Afro-Pindorama peoples, through their encompassing cosmological grammars that interweave knowledge and territory, know very well.

Sandra Benites tells us that her grandmother in Mato Grosso do Sul taught her not to believe in paper: “Paper is blind, writing has no feelings; it doesn’t walk, it doesn’t breathe, it’s dead history. Although it is part of our lives today, we must be careful with paper”. Davi Kopenawa, from the perspective of the Amazon Forest, drew attention to the non-indigenous obsession with writing and books: “They never stop staring at the drawings of their words stuck on paper skins, and circulating them among themselves”; restricted to this mode of communication, white people “study only their own thoughts and thus only know what is already within themselves. But their paper skins neither speak nor think. They just lie there, inert, with their black drawings and lies.” In his book, The Falling Sky, written in partnership with Bruce Albert, the Yanomami shaman concludes: “By far, I prefer our words!” Ancestral sayings have never been drawn into books: “They are very old, but they are still in our thoughts today. We continue to reveal them to our children, who will do the same with their own children after we die”.

Kopenawa is aware that books are the privileged means for the production and dissemination of knowledge in our society. In such a manner, they are also agents of delegitimization of language forms other than written. However, he chooses as a strategy to stick his words on “paper skins”, challenging the regime of visibility and invisibility imposed by us, the Napë. It is up to the Napë, editors and publishers, authors and readers, to overcome writing as opposition and epistemic destruction, and to invent modes of shared writing-listening-reading productions. While the spaces of power are not yet occupied by those who have been marginalized, it is a duty for us to transform our advantages and privileges into shareable techniques.

Recognized as authorities in the dissemination of reliable knowledge, books and the power dynamics surrounding them have normalized the idea that the intellectual production of a restricted group of people represents a supposed entirety. Thus, knowledge separated from the land has been the only knowledge considered valid. Extending this critique to the way written texts have, on multiple scales, sanctioned violence against subjects and territories, and understanding books as operators within structures of violence, is in many ways an initial but fundamental step to overcome this deadlock.

By demystifying the book as a neutral object and exposing it as a western instrument laden with coloniality, the importance of situated and traditional knowledge for editorial alliances becomes evident and urgent. The demarcation of pages in this bibliographic occupation becomes essential in order to broaden the possibilities and variations of reading, writing, listening, learning, sowing, cultivating, and reforesting. In the Afro and Indigenous voices written in Terra, multiple worlds, usually inaccessible to most people (since they are manifested through plural cosmo-languages), irreversibly transform our practices with perspectives that surpass modern logic. After all, as Gersem Baniwa argues, “Indigenous protagonism in the production and dissemination of plural scientific knowledge opens new perspectives and concrete possibilities for dialogue, sharing, cooperation, interethnic collaboration, intercultural, interepistemic, and interscientific complementarity between different conceptions, worldviews, logics, rationalities, and their subjects.”

Antônio Bispo dos Santos reflects on his journey from orality to writing and invites us, those of us who only know how to write, to learn and unlearn with printed oralities: “Whoever reads this book will learn to speak, and I who wrote it will learn to read,” stated the quilombola author regarding the book A terra dá, a terra quer, published by PISEAGRAMA in a partnership with UBU; learning to speak as a celebration of returning to the land and as a recapture of storytelling that brings us together and allows us to dream.

Bispo points out that his writing is deeply intertwined with the orality that underlies the relationships in his community. “I went to school from Monday to Friday; on Saturday and Sunday I stayed with my older people, writing letters, reading medicine labels, reading everything written on paper that my people could find.” He learned from his elders not only the importance of plowing the fields and caring for the ground beneath his feet, but also of traversing the colonizer’s universe, as he often says, appropriating their language in order to translate it for his people and, on the other hand, also teaching the city people, the people of writing, to listen and to speak.

“The time of clay represents a period in which the school as an institution did not yet exist, and in which Indigenous education took place through chanting, through spoken words. There was no writing, but there was memory”, explains Célia Xakriabá. When master of clay construction and painting of toá, Libertina Seixas Ferro, was suggested by a non-indigenous student a solution to the uncomfortable and laborious need to reconstruct houses that were crumbling down due to the rain, she responded: “No, son, your proposition is dangerous. The house needs to come undone in four or six years so I can keep teaching my children and grandchildren!” A clay house is not just shelter in the semi-arid region, but a material, oral, and memorial form of transmission of knowledge.

Reading to learn how to speak, writing to learn how to read, listening to learn how to unlearn, building to continue teaching, getting it undone to live through it again. To paraphrase Sueli Carneiro, the contract written and signed by one side of history only has made every white person a beneficiary of racism, speciesism, ethnocentrism, and heteronormativity – which does not mean that all these (white) people are signatories to that contract. That’s precisely why alliances can be made.

Peruvian anthropologist Marisol de La Cadena teaches us that alliances are “different sides of the same coin”, corresponding viewpoints of worlds that are not the same. At the same time, alliances enable a destabilization of linear grammars and violent naturalizations, making plausible the possibility of a single word holding distinct meanings in different worlds. Even though they might often seem fragile footbridges, editorial alliances can enable bridges between diverse and diversified worlds, rather than segregate them by their differences.

If the imperative of editorial policies has been to abstract the land, neutralize affections, train bodily experiences through writing, and restrict to a few individuals the community capable of publishing, then thinking them in a cosmopolitical way is precisely an attempt to overcome coloniality. It is about giving due importance to encounters, negotiations, dialogues, and disputes that resonate from shared life, from the constant, urgent, and necessary attempts of alliances between the worlds that make up the world. The essays gathered here address the multiple relationships the earth has with the city, with climate, with politics, and with the body, from the perspectives of quilombos, indigenous territories, urban peripheries, settlements, extractive reserves, recaptures, forests, semiarid regions, favelas, terreiros, and reinados.

Thinking of editorial policies as a cosmopolitical proposition involves not only humans, or particular human types, but the entire terrestrial collective, because a book means much more than what we are used to believing. Not only because books are indeed true “forest skins” or urihi siki manufactured by crushing a large number of trees; and trees provide food for the spirits of bees and other winged animals, as an indignant Davi Kopenawa points out; but because a book, this anthology, cannot be taken solely as just another editorial and industrial product like others (even though it is that as well). There are many bridges and footbridges being constructed on the pages of Terra. Listened-to, written, and printed here – not without the awareness of inherent contradictions – are concrete struggles against racism, genocide, epistemicide, gender normativity, ecocide, and other forms of violation that continue to ravage villages, quilombos, terreiros, favelas, and bodies, produced at the expense of many human and non-human lives. But here are also speculations, sown with feet on the ground, about the impasses of our time — the Anthropocene —, crucial for an urgent re-engagement with the land and the care of the Earth, as well as for the expansion of our narrow imaginaries of coexistence.

–

PISEAGRAMA is made up by the editors Felipe Carnevalli, Fernanda Regaldo, Paula Lobato, Renata Marquez and Wellington Cançado.

Jaime Lauriano is an artist who won the 20th Contemporary Art Festival Sesc_Videobrasil and the 6th Marcantonio Vilaça Prize. He is part of the Pinacoteca-SP, MAR-RJ and Schoepflin Stiftung collections.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in the book Terra: antogia afro-indígena (PISEAGRAMA + UBU, 2023) and translated into English by Brena O’Dwyer.

How to quote

CARNEVALLI, Felipe; REGALDO, Fernanda; LOBATO, Paula; MARQUEZ, Renata; CANÇADO, Wellington. Listening-writings (and vice versa). PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, December 2023.