Prophecy of Life

Text and images by Ventura Profana

We’ll see things in their true scale. Rivers will reclaim what is theirs, the oceans will reclaim what is theirs, the forests will reclaim their territory, and we’ll return to our primal nature. And how do we return to our primal nature? By becoming travesti! Trans people are not just human; they are supernatural. And to achieve all this, toxic masculinity must fall.

Not long ago, one of my bois questioned me on how I see myself now and how I think I will see myself in three years. “Sis”, I replied, “we are working on a world project for 100 years from now!” From a very Cartesian point of view, what troubles us? Bolsonaro? Our problems go far beyond that! It seems like everything boils down to that all the time, as if every problem in the world could be summed up in a political post. You said three years from now? In three years, I want to have a few small things accomplished – my album released, a thousand places visited, and more – but my main project is bigger, much bigger than that!

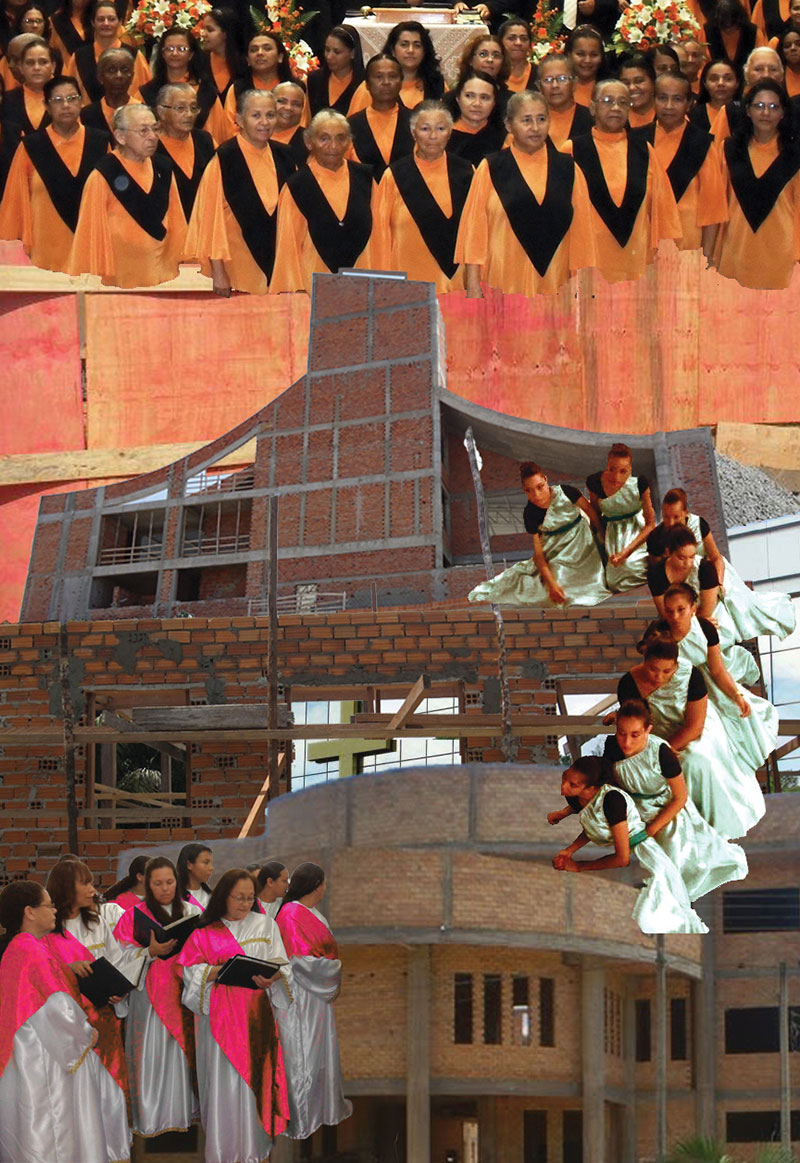

I have a world to build. And I’m not waiting around for this world to end before I begin to build the next – we, travas,(1) have already begun that. I am building a church, a congregation for Brazil. In 100 years, I want a nation with queens in command. A travesti president. That’s what I work for, to see a travesti(2) climbing up the Planalto(3) ramp, grabbing that damn sash and shoving it up her ass. I want her to do whatever she wants with that sash. Wear it as a top, as a bathing suit… that she goes completely naked, if she wants! That she makes her own trikini out of it, if she wants!

The Bible was translated into Portuguese in 1819, 200 years ago. Yes, short time and a whole lot of damage caused. But who is to say that in another 200 years our Bible will not be the best-selling book in the world, instead of the men’s Bible? It is going to be the Book of Life, the Book of Queens. I know, I am a very stubborn Capricorn, and I was born this way, always wanting a lot of things.

I was born in Salvador, but my family is from Catu, a town bordering the Bahian(4) backlands. The economic flow of this region was focused on the extraction of oil and minerals. Everyone around me worked for third-party providers of Petrobras(5) and aimed at working on the platforms offshore. We moved to Rio when I was 11; I lived in Catu until then.

My roots, my childhood memories, the most beautiful and dearest things I carry with me belong to that place. The church of Catu, I love it to this day. All my childhood friends and loved ones were from there. And then, there’s the sunset. I was born at sunset and when I think of it I always come back to that moment, that momentary explosion when the sun becomes moon and there’s an outburst of colors! Yes, the most beautiful things there are; every pretty little corner, they all bring me back to Catu. But it took me a violent and profound adaptation process in Rio de Janeiro to understand that.

Much later, when I started to study evangelicalism and realized that my work and my life were deeply intertwined with Christianity and evangelical doctrines, I already understood my blackness. It was then that I tried to understand how and when my family started to demonize what comes from blacks. What is faith? The Black faith? Things only started to make sense to me when I found out that my great-grandmother had been born and raised in a terreiro(6) and then gone through a very peculiar process of catechesis and evangelization with an American missionary. That took place when Petrobras arrived in the city and began exploiting the land.

Most of my family is protestant. Some attend the Baptist church – more traditional, pompous, of North American origin – while my father’s family is more of the “reteté“,(7) of stricter and more severe doctrines, like the Assembly of God and the God is Love church, where the girls can’t have their hair cut or wear earrings – that’s the mood.

The black bodies that left the Candomblé terreiros and migrated to these churches, like my great-grandmother, keep the memory of (that) spiritual manifestation. It’s strange to attend such a service. “Doll! What’s going on? Why is the crowd whirling around? They’re falling to the ground, their hands on their heads!” There are several elements of Candomblé that are present in neo-Pentecostal churches. Even the status of trance – the body that goes into a trance, that is touched and receives the spirit of God.

My arrival in Rio coincided with the beginning of adolescence. It was when I started to perceive myself as a strange, fairly horrendous body: I thought I was hideous, grotesque. I was fat, from Bahia – an stigmatized region – and had an accent that could easily give that away, while everyone else seemed so “perfect”. In Rio, even in the suburbs, everyone was somewhat Projac(8) material. It was tough being this body. For a long time I thought it was awful to be from Catu. I told a thousand lies not to be that person. I wanted to be a carioca(9) like everyone else in Rio. Obviously, I was never successful, but coming to Rio allowed me to find myself, to catch a glimpse of the infinity I could be – and already was.

In church, however, I wasn’t an aberration. By denying myself and taking up my cross, I became a strategic asset, because my faith was explicit, vividly embodied. If you are suffering, denying and sacrificing yourself, if everyone can see your pain, your tears, then you are useful. And I was very useful. I started to do things in the church, to have power; I was taking on great responsibilities.

Like many others, the Nova Vida church operated in the building of an old cinema. When we arrived in Rio, we visited several churches before we found the one with very powerful red armchairs. When I saw it, I had no doubts. “This is it!” I said to my mother. Everyone was kind of nice. Phony, but nice. My aunt lived with us at that time, and we got involved in organizing a party, a sort of fair. “Celebrating a new life in Christ.” And that was that! Two weeks before the party, I was at the church every day with the older ladies, preparing shrimp to make bobó,(10) preparing meat and cassava, and conversing with the pastor. I began to engage, and the church became the best place in the world for me.

I went to a school that had lots of “queers”. It was horrible! I used to say, “Damn it, it’s the devil right in front of me!”. I preferred going to church because there I had everything under control. I started to work a lot in the church, preparing the services. I would choose the theme, talk to the pastor, set the date, and work on putting them together. In Catu, my mother was involved in the programming ministry, so I already had some experience with church entertainment. My uncle Flávio wrote many plays, and we would always be in them. I had everything!

I always played a beggar or a sick person. And after I arrived in Rio, I would usually play the devil. My mother would play the macumbeira.(11) In the church plays, there was always the macumbeira, the indigenous, and the black, always characterized in rags. Those were our roles. Still, being able to act was everything! I couldn’t do choreographies because they were only for the girls, for the “sis” gender. But children could do them, and while I was still a child, I would nervously attend the sises’ rehearsals.

The name of the girl who put the choreography together was Suleide. Suleide also sang, and when she sang, she was in close-up view. Suleide was a pop diva in the church. Besides loads of accessories and clothes, she wore the highest heels you can find. That was the Sunday night singing look. Those were the things I liked most when I was in church. They moved me, I lived for them, and in my sophomore year, I would skip school to go to church.

Failing in school changed my life. That’s when I truly started living. My mother said she would beat me if I ever flunked, so I didn’t tell her that I had to repeat the year. I dropped out of school but kept on finding things to do to keep busy. I went to study design, art, and did a lot of other things to make it look like I was in college. But that would not resolve the diploma mess since I never really did go to fucking college! Then I did the only thing I could do, I ventured out into the world.

As time went by I gradually built the beauty I am today. I began my self-registration process. At first I thought I was horrible, ugly and fat, until one day I just said to myself: “Never mind that! There’s something here that is beautiful”. If there were guys out there wanting it, there had to be something good in this body! And it turns out it was my butt. I started taking photos of my butt, and that made me feel stronger, and at the same time I started to write. Those two things, the capturing of my butt and my writing opened up a channel of transformation to me.

In 2012, I posted my first butt photo on Facebook and people were blown away. It was chaos, but it was a great capstone for me: I branded myself with that. After that, I was always taking pictures of my butt, everywhere I went. I have many pictures! I love them! I even did a series positioning my butt in squares, using several air-conditioned frames.

In 2015, I won a grant from the Oi Kabum! Escola de Arte e Tecnologia (Oi Kabum! School of Art and Technology) and went to Belo Horizonte. I learned the basics of editing, gained a writing style with more freedom, and began experimenting. I managed to finish my book, but by the time I released it, I found myself not quite fond of it anymore. I had fallen for the newer things I was writing – they were freer, edgier, and more politically charged. As I left Rio to launch the book in Belo Horizonte, I departed as one person and arrived as Ventura. I embraced the name Ventura in early 2016; before then, I used to sign my writings as “by Ventura”. It just wasn’t the same thing.

Upon reaching Belo Horizonte, I found myself in the company of trans women and men, and together we experienced a beautiful healing process. That was the same year Beyoncé dropped Lemonade. Later on I understood that my own journey reflected the essence of Lemonade. My process involved herbal baths, splashing in waterfalls, puffing some green, grooving to good vinyl records, falling in love and being loved… I had gone through it all. And then I sent my book out to the world. That’s when I became Ventura Profana, and in Belo Horizonte, nobody knew me by any other name.

As I returned to Rio, the struggle to make others understand was real. “Don’t call me that! That’s not my real name! I’m not her anymore!” I had to push back the people who couldn’t take my true self. I came to a turning point where I simply had to say “Fuck it!” and move on.

The night I set off for Belo Horizonte, I had a terrible fight with my mother, and even told her not to come to the book launch. But she is the most important person in my life, the one I love the most, my guiding light. And she has had her fair share of right calls, even when she claimed that art ruined my life. “The second you started studying art, your life ended!” she would say. Well, indeed it ended, but only so another one could begin.

My mother is a coherent person and my life journey brought emancipation to her as well. Nowadays, she stands strong with her feminist convictions, opposing many things, also within the church. During my stay in Rio, I tried my best to be close to her, back in the family home, bridging the gap between our worlds. It was a special time to me; it was nice to wake up every day to hymns of praise. I couldn’t rid myself of the church. It was always there, right in front of me, right within me.

Even after taking different paths, exploring new places, and gaining more knowledge, the presence of the church went on confronting and hurting me. I had to come up with survival strategies that eventually became a plan of salvation. And that’s where I stand today, crafting a plan of liberation that stemmed from and is sustained by the study of methodologies and the history of evangelicalism in Brazil.

It’s a well-known fact that every poison carries its own antidote, and that’s what I’ve been working on — creating that antidote. These days, I spend roughly 70% of my time pondering over that while I listen to hymns of praise. My Spotify library is filled with the entire discography of Ana Paula Valadão,(12) and I’m cool with that. That actually empowers me instead of weakening me. As I consume the poison, I find myself getting stronger.

Recently, I took a trip to Bahia, accompanied by folks from the axé(13) tradition. I attended the Iemanjá(14) celebration and realized that most of the people there were white. And they were embarrassing themselves trying to embrace some sort of mermaid obsession vibe. They were not really celebrating Iemanjá, they were just white girls showing off their mermaid tail costumes. That made me upset and led me to realize a new exodus is called for. We, black women, need to break free from the compromise we admit to The Lord and return to our roots, to Kalunga(15) and our terreiros. At the same time, I understood that the way I’ve learned to live has a Christian foundation, that I was losing strength getting away from the Bible. I was distant from the place that brings me back to my center and gives me strength, and that I had been completely denied of.

It’s a peculiar puzzle because I walk by faith, yet that faith is constantly being torn down and rebuilt. I can find religion in anything – absolutely anything. I go on piecing together this sacred place, a place for the body seeking spiritual fulfillment. I do strive to be spiritually fulfilled, and I firmly believe that this is the only way to truly fight the battles of a black travesti person: to fight with spiritual weapons.

I always say and I always sing: “Arm yourself with spiritual powers”. Firearms are not going to save me – let me rephrase that, in certain cases they might be useful. So, we also need to ponder on warlike knowledge. When I think about the church I am building, I think of a church that will understand, exercise and relate to any and all kinds of knowledge, combative knowledge inclusive. The foundation of our congregation is travesti. In addition to that, any and all sorts of knowledge interest me and the constitution of this congregation.

It was during a TransVest(16) birthday, at a bar table with Indiana Siqueira, Luciana Vasconcellos, Titi Rivotril and many other wonderful travestis and transmen that I realized — I looked around, and for the first time I understood: God is travesti. If we are made in the image and likeness of God, and have two biological species representations (male and female), then God can only be a combination of the two. Therefore, God is a travesti or a boyceta. And that is what takes us into the field of divine infinity.

In 2016, I did a performance called Bixa Apocalipse,(17) in which they roamed through Rio and held signs “Repent, the end is near”. I stayed in the frenzy that the apocalypse had arrived and that we, travas, were the ones raptured. When these people departed from this spiritual realm, sadness, monotony, and frustration would take over this space, while we would be exploring galaxies, painting, parading down never-ending runways in the universe.

The arses of those who stayed would be sewn, so that they would throw up their wastes and feel the taste of censorship and the scent of death. There was a hint of that scenario that we have actually seen happen these days. After ‘Bixa apocalipse‘, ‘Bixa a coisa é séria’(18) came. Here I talk about how serious it is to be who we are and to have come from where we came from. These two texts mark the moment when I embark to another path of writing, of reappropriating the Bible. I began to call this process “The obsolete life of sub celebrities”, which will later become “The book of life”.

Afterwards, I put on a new performance, a procession, where I joined other travestis in carrying a red cross while singing “Holy Spirit, Holy Spirit that descends like cloven tongues like as of fire, come as in Pentecost and fill me anew”. It’s this beautiful chant that can be freely translated to “I Will Sail”. We were all wearing panties with the Universal Church logo and the phrase “Universal is the Queer Kingdom”. Later, I decided to do another version, the “God is Trava Pentecostal Church”, with the logo of the “God is Love Church”. Everything was done with the help of other travestis, and it brought such a powerful energy to the whole work. Rainha Favelada wore a red veil and held a candle while praying. I got down on all fours over the cross, as if crucified that way, while the other girls prepared the grout and began building a church deep inside me.

We were out there the way we wanted, at the peak of our faith, of the ecstasy of life, making an impact. All the girls were talking about nails, Linn da Quebrada was considering ‘claws’ and Lyz was debating manicure power. We were all thinking about that and a lot of other things. Around the same time, Matheusa wrote ‘O Rio de Janeiro continua lindo e opressor’(19) and after she wrote ‘Trabalho de Vida‘,(20) her last work.

When Matheusa was murdered, we were already in motion to refuse the killing and oblivion of our own. We began to discuss the Prophecy of Life – a lifelong work that left quite an impression on me since it was about the story of her life up to that point; her own Genesis of sorts. If we are going to build a trava Bible, Matheusa’s story ought to be the foundation stone.

A while ago, I used to spend a lot of time talking about the parallel between the crucifixion of Christ and our own condemnation as dissident bodies. The cross represents salvation for some and damnation for others. I used to talk a lot about the cross, something I no longer do today, because it seems much more urgent to say: “Behold, all things are made new, all trava things are made”. We need to discuss the post apocalypse! We need to start prophesying. The girl writers are prophetesses; there’s no time for wakes and death talks anymore. You can just turn the news on for that!

I was raped when I was as a child in Bahia, more than once and by more than one man. For me, it was very confusing to deal with it. I thought that being raped hadn’t changed anything in my life because I considered myself a happy person. I didn’t even think about it when I was depressed, disliking myself, and wanting to die.

But the rape not only changed me it also connected me to my mother and grandmother, and probably to my great-grand mother as well. This is also a way to understand the whitening process in Brazil as a public policy of colonization. We are all daughters of a ‘Brazil (of) rape’, descendants of a history of sexual violence. When I try to understand the color of my skin, for example, I trace it back to this traumatic event. I am black with a lighter skin. Why is my skin light? Because I am a daughter of a country where rape was endorsed by public policies. Some guy showed up, took my great grandmother in the woods, violated her repeatedly, and there, here I am. It’s a heavy mess. It’s no wonder we’re still constantly trying to find ways to alleviate the pain.

All of this starts to make a lot of sense as I piece together my puzzle. Oil, religion, rape, skin color, demonization of our spiritual temples, the men’s world. Today, I believe that “man” is a synonym for sin. Masculinity is the sin. Patriarchy is the root cause of all that is wrong. We’ve all been condemned to this toxic masculinity. We are condemned to it from birth. Even men are condemned because toxic masculinity is a sin that saddens the soul. It’s abominable, it denies us a complete spiritual connection with what is divine – with the divine essence.

For over 500 years, we’ve endured this war, this extermination plan against everything that relates to black, trava, indigenous, and dissidents. Against everything that isn’t white, heteronormative, or male. But despite this plan, a generation of prophets has risen, fantastic travas with an unwavering fire, a divine calling. In 100, 200 years from now, when we are in power, when the world belongs to us, the trava queens, I envision a world of forests all around. Plants and animals taking over the cities, that concrete everywhere. I will gracefully walk barefoot, in a beautiful, flowing skirt, with my hair flowing in the wind, without so much makeup on my face – just a hint of color, a more natural girl.

Nature will reclaim its space. The sea will reclaim what was taken, restoring balance. We’ll see things in their true scale. Rivers will reclaim what is theirs, the oceans will reclaim what is theirs, the forests will reclaim their territory, and we’ll return to our primal nature. And how do we return to our primal nature? By becoming travesti! Trans people are not just human; they are supernatural. And to achieve all this, toxic masculinity must fall.

When the church was built inside my body, it truly began within myself. This happened in 2018. I went to São Paulo, made the video “Life Prophecy”, and started talking about prophesying lives. Everything I learned in the church, I have been putting into practice, but after a tumultuous process of centrifugation, after much destruction. When I talk about the plan of salvation, I draw this from the Baptist and the Presbyterian churches, which will always discuss the plan of salvation, as they start from the premise that we are all condemned and that there is a salvation plan for the chosen ones, for those who sacrifice themselves. This plan often involves submitting oneself to a process of purification and whitewashing.

I learned about this since I was very little. My mother and grandmothers brought me up to live this way. I was raised to be a pastor, a music minister, a person who relates to the Bible, to the word of God. I fulfill many of the dreams and expectations led by my women ancestors. At some point I realized that, and today I am able to use some of this knowledge/wisdom. But I still have so much to learn, and others already know so much more. That’s how the church is built, by what I bring and by what each and every other woman brings; just like the Spirit that speaks in each of us, intimately, in a unique way.

How to keep your faith strong? How to take care of the field of faith in people’s lives? What are our references? They’re out there, we just need to look for them. When we try to understand how faith is built — how faith is cared for and experienced — in a pajelança,(21) for instance, our perceptions will expand. We can also experience faith in gratitude, in speaking with and praying for the Earth, in connecting with it, in taking care of ourselves with healing herbal baths. I learn all this from black women, my indigenous relatives, my grandmothers and my mothers.

I do not despise any spiritual practice and set of knowledge different from mine. Nowadays, for instance, I try to be a carranca (22) (following the advice of Davi de Jesus)(23), to come in front of the ship, breaking water and breaking wind, moaning and screaming, scowling and chasing away evil spirits. Our church is going to have a lot of carrancas! At the entrance there will be an altar for Exu. We can’t deny that. It’s a necessity; there’s no way out of it. We can’t deal with these energies and forces without proper care.

The Tabernacle is a kind of sanctuary that worked as an ambulant temple during the crossing of the people of Israel — arbitrarily called the people of Israel — through the desert, which lasted 40 years. It was a nomadic movement. The people walked on and off, and when they stopped, they set up the Tabernacle, a series of tents where the ark of the covenant was, and where the priest communicated with God. At that time, it was believed that the relationship between men and God had been broken, so only the priest could provide that kind of service. Biblically, churches are not temples. What the Bible states is: “Where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am among them.” That’s the church.

I think a lot about what we are going through at the moment in Brazil; a moment of persecution in which we are targeted, our faces are exposed and, fearing the face of our own death, we must evoke all the courage within the very depths of ourselves. It is the existence of those who walk down the desert, who have survived this far by a miracle. And the black women, the travas, those with absolutely nothing, those are the ones who really work miracles. We are miracle workers in our day-to-day life. We multiply bread, we turn water into wine, and since we always have to run, we can walk on water. That’s why it is so important for us to have a temple.

It is important that a trava claims the place of the shepperd. Because the Lord is a shepherd. When I become a shepherd, I have the power to end the Lord. After all, what is the Lord? The Lord is the lord, “the” lord, the essence of authority. We have to kill the lord. When I embrace the role of a shepherd, I inherently challenge the Lord’s position. And being a shepherd requires absurd responsibilities. The shepherd spiritually guides people, and this is a damn great responsibility.

I think I have had a calling, I feel called to this work, I feel like a channel. Others share this calling, and I am only one more among the chosen ones. But I have a responsibility — a job to do, my love, that might get me a good beating, if I don’t get it done. I don’t have a choice in the matter.

One of these days, a girl said to me: “Ventura, you are taking on the aesthetics of the choreography, sisters, right?” I was wearing a kind of a sport-believer outfit, really.

If there are wolves in sheep’s clothing, it is crucial that we are then lambs in wolf’s clothing. For me, having a wolf’s skin means embodying a church, becoming the face of the church, a living temple, a true believer. I want to look more and more like a believer.

The Pharisees and the false prophets offer salvation, manipulating the masses for their financial gains, shaping them into a fascist army. They are blinding our people. There is a work in progress, of blindness and maintenance of enslavement in our families, coming from the spiritual realm. The work of conversion aims to achieve that goal: you sit at the table of those who kill you and unknowingly endorse the extermination of your own kind.

If you are the target of those who kill and then become the one who kills instead, you gain power over the cross, over who dies. When you have the power to create the plan of salvation, you are saying who is doomed and who is not. I want to compete for power over salvation, over the message of light, over right and wrong. What do we do with the sheep? Why do we raise them? To slaughter them. This is why I believe it is vital to claim the altar and the pulpit for ourselves. I’ve always wanted to be a spy, and this role of espionage is no different – I must infiltrate and conceal my true self.

Who holds the power? I hold the power! I am in power in moments of chaos, when I am dressed in wolf’s clothing. The church cannot touch me; I am the church! With the Pentecostal vocabulary, I can connect, converse, and persuade. I can prevent a believing person from causing me harm. Can you? I have nothing to fear, my love. I have only love; I have no fear.

–

Ventura Profana is a singer, writer, composer, performer, and visual artist. Born in the mysterious depths of Bahia, she is a carcará, a Black transgender woman from the Northeast. Indoctrinated in Baptist churches, she investigates the implications of Deuteronomism in Brazil.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in the book Terra: antogia afro-indígena (PISEAGRAMA + UBU, 2023) and translated into English by Monyque Assis Suzano in collaboration with Maria Bernadete Morosini.

How to quote

PROFANA, Ventura. Prophecy of Life. PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, December 2023.

Notes

1 Travas is short plural form of travesti, Brazilian and Latin American trans gender identity

2 Travesti: individuals assigned male at birth embracing a feminine gender identity, challenging norms prominent in Latin America, particularly Brazil and Argentina

3 Planalto: short for Palácio do Planalto (Planalto Palace), the seat of the Federal Executive Power, where the Presidential Office of Brazil is located

4 Bahian: related to the state of Bahia, native to or an inhabitant of Bahia

5 Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., a Brazilian publicly-held multinational corporation specialized in oil, natural gas and energy industry

6 A terreiro is a sacred space or temple for the practice of the Afro-Brazilian based religions called Umbanda, Candomblé and Quimbanda.

7 ‘Slain in the spirit’ phenomenon.

8 Projac was the former name of Estúdios Globo, the primary production facility for Brazil’s largest television network, Globo.

9 Carioca is a term used to refer to someone who is a native of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It can also describe the distinct culture, style, and way of life associated with the city and its residents.

10 Bobó is Brazilian dish featuring shrimp and cassava in a flavorful stew, rooted in Afro-Brazilian culinary heritage.

11 Macumbeira is a female with knowledge of or involvement in macumba, a syncretic Afro-Brazilian belief system. The term’s implications vary based on cultural perspectives.

12 Ana Paula Valadão is a Brazilian Christian worship idol, singer-songwriter, and pastor, with over 15M global worship album sales and worship gatherings of up to 2M people.

13 Axé originated from the Yoruba term àṣẹ, and signifies “soul, light, spirit, or good vibrations.” In the Candomblé religion, axé embodies the spiritual power and energy bestowed upon practitioners by the pantheon of Orishas.

14 Iemanjá or Yemanjá is a prominent deity in Afro-Brazilian based religions, particularly in Candomblé and Umbanda. She is often devoted as the ruler of the sea, embodying qualities of motherhood, fertility, and protection.

15 Rooted in Afro-Brazilian traditions, Kalunga encompasses the spiritual realm of ancestors and the profound connection to the Atlantic ocean.

16 TransVest is an NGO that seeks to empower and include the transgender population in society through education, art, and sports

17 Freely translated as “Queer apocalypse”

18 Freely translated as “Queer the thing is real”

19 Freely translated as “Rio de Janeiro remains beautiful and oppressive”.

20 Freely translated as “Work of Life” published in the Art Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

21 Pajelança refers to traditional Amazonian healing rituals conducted by indigenous shamans, known as pajés, involving a blend of spiritual practices and herbal remedies for holistic community well-being

22 Carranca means scowl; it refers to a river craft figurehead believed to possess protective powers against evil spirits for boatmen

23 A traditional Minas Gerais visual artist, performer and barranqueiro poet, who recites rhymed verses accompanied by a viola, reflecting the region’s culture and landscapes