Village-School-Forest

Text by Isael Maxakali and Sueli Maxakali

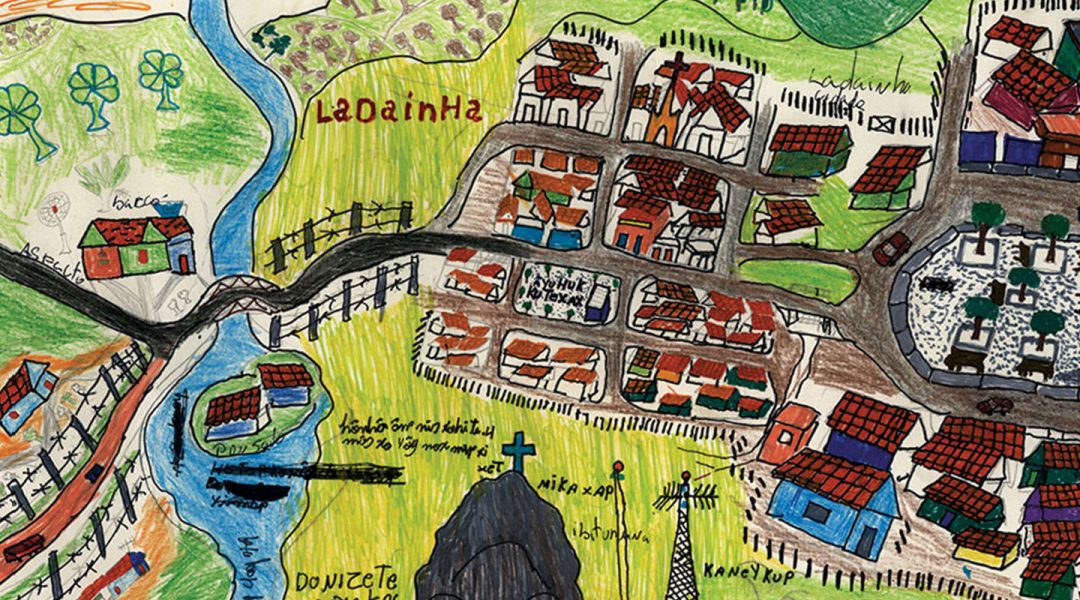

Mapas, drawings by Donizete Maxakali, Totó Maxakali and Zé Antoninho Maxakali

We hope to get this land back, to earn the right to it. The earth is alive, it speaks, it looks at us and screams, because it needs to be healed, it needs treatment. The farmers don’t listen to the land screaming, even though its cries for help. That’s why we want to reforest this land and make it the Village-School-Forest. In an Indigenous village, everywhere can be a classroom

The Tikmũ’ũn have always been here, in these lands that you, white people, call the Mucuri Valley and that we call kõnãg mõg yok, “where the river runs straight”. There were many of us in the old days and we lived alongside the river. We would build a village, hunt, fish, and dance with the yãmĩyxop, the spirit people, and after a while the elders would get together and decide to move.

We are a traditional people, originally from these valleys. In the past, we lived in several villages, more or less distant from each other and always following the course of the rivers: when one of us died, we moved villages; when a conflict arose, we moved villages; when it was difficult to hunt and fish, we moved villages. We made large gardens and planted banana trees, potatoes, cassava, yams, which we ate with the meat we hunted or the fish we caught.

There used to be no whites here. When the first whites arrived, they were very angry. They killed many Tikmũ’ũn and brought on disease. The ãmãnex xax ãta, “priests in red clothes”, brought cloths for the Tikmũ’ũn, cloths that spread measles and smallpox. When one fell ill, we separated in fear and fled into the forest. That’s what happened in Itambacuri, in the state of Minas Gerais. The Tikmũ’ũn left, going up the Jequitinhonha Valley, where the city of Araçuaí is today. Others fled to Minas Gerais from the south of the state of Bahia, as did the Botocudo,(1) who went up from Espírito Santo until they reached the city of Teófilo Otoni. When they met, the Tikmũ’ũn and the Botocudos fought.

The yãmĩy nãg, the child spirit, always warned us when a threat – like the whites or the Botocudos – was approaching. At night, he would come, knock on the wood of his father’s house – tok tok tok tok – and warn him: “Father! Father! You must leave! Take the Tikmũ’ũn away from here! Hide! The whites are coming to kill you!”. Then the Tikmũ’ũn fled again. Finally, we arrived at the place where the villages of Água Boa and Pradinho are located, in the municipality of Santa Helena de Minas, and we hid under a very high rock, in the place we call mikax kaka, “underneath the rock”.

The whites were already everywhere and were chasing us, wanting to kill us. When the Tikmũ’ũn noticed that they were approaching or when they heard an airplane passing by, they would run into a cave in Água Boa, where several bats lived, and wait. The whites would leave, thinking they had finished with everyone, but the Tikmũ’ũn were still there, hiding. After some time, there was no way out of it and the Tikmũ’ũn had to get involved with the whites. They brought cachaça,(2) fabrics, knives, scythes and distributed them among the Tikmũ’ũn, who didn’t know about those things. The whites would bring a knife and exchange it for land; they would bring an ox and exchange it for land, they would bring cachaça exchange it… The whites would take pictures of the men and women and show them, saying “Here is your soul (koxuk)! If you don’t get out of here, we’ll destroy you all!”. And the Tikmũ’ũn, afraid of losing their yãmĩyxop, fled.

So, the farmers took over our lands and cut down all the forest. We, growing up in Água Boa, saw the big forest with our own eyes. But over time the farmers cut down everything and the forest turned to grass. We Tikmũ’ũn had to choose: either we lost our land or we lost our language. We’d rather lose the land than lose the language. If we had chosen to lose our language, we would no longer exist. We would all have disappeared, like many other peoples who lived here.

Zé Antoninho Maxakali

At that time, people from the village of Pradinho would come to the nearby village of Água Boa to buy sell their produce. They came to buy sugarcane, corn, and beans, but they couldn’t go where they always went, because in the middle, between Pradinho and Água Boa, there were farmers Laurino, Arlindo and Abana-Fogo. Those farmers were living there, and together they did not let the tihik, the Indigenous people, cross. They were armed and mounted on horses, with weapons strapped to their backs.

When we went to the Pradinho river, we couldn’t bathe. We would bathe in the hidden waterfall, and soon we would come back. Halfway between Água Boa and Pradinho, we found farmers, who at the time owned our land. It was difficult for us tikmũ’ũn children. The waterfall and the river were beautiful, but we couldn’t bathe because the gunmen were very violent. The boys from the Pradinho villages all came to bathe in Água Boa. When they came, the children of non-Indigenous people threw stones at them with slingshots. Then the tikmũ’ũn boys started to do the same, and they ran.

We fought to take back the strip of land that was invaded by farmers. It was very difficult at that time; there was a lot of violence against us Tikmũ’ũn people, and many deaths, too. There was an audience in Bertópolis about the land, and the yãyã went, the elders, relatives from Bahia who helped defend the Tikmũ’ũn, along with the chiefs of Água Boa and Pradinho. During the hearing, a relative from Bahia ran to hit Captain Pinheiro’s head with a stick, but the police wouldn’t let him. There was almost an ugly fight. In the end, they managed to demarcate(3) the land with the help of a deputy who was supporting our fight. We had a big party, and all the Indigenous people from Pradinho and Água Boa came.

When the land was demarcated, in 1996, it was already completely deforested: the farmers cut down the wood, sawed it and were raising cattle, and many tihik had already died there. The elders told this story every time we passed by. After the demarcation, we built a village near Pradinho, where we planted cassava, beans, and corn – there was also a lot of papaya. We built the village there, stayed a while, and then went back to Água Boa.

Donizete Maxakali

In 2005, after serious conflicts (which continued for a long time, even after the demarcation) involving farmers and some of our relatives in the village of Água Boa, we had to hurriedly leave the land where most of us were born and raised. For almost two years we were provisionally camped in the municipality of Campanário, while Funai(4) looked for a solution for our group. At that point, we no longer wanted to return to the lands of Água Boa, as we feared new conflicts. That was when Funai proposed that we go to a new land.

For months on end our leaders traveled in search of a land that would meet the demands of our people for forest, river, and fertile and flat land in which to build our villages and plant our gardens, as in the old days. The search was not easy: we found large plots, but they had no forests and were very far from our relatives’ villages and our traditional environment, the Mucuri Valley. Other lands were closer, but the terrain was very mountainous. Over time, the pressure to decide our fate increased, as there was a risk of the resources returning to the State.

At that same time, four of our children were hospitalized in the city of Governador Valadares with hepatitis, which scared everyone and increased the urgency for us to move. It was in that context that, on another of our visits, we arrived at the municipality of Ladainha. The land, which we already knew, was not what we had dreamed: there was no water, and the terrain was very mountainous. But there was a forest, there were wood and palm trees for our men to build houses and bamboo for the women to weave bags. There was also a river close to the territory and the possibility of expanding the land in the future in order to reach it. That’s how we decided to stay and in 2007 we created our Aldeia Verde, the Green Village.

Many years have passed since we arrived there and much has changed. Our population, which at the beginning consisted of 100 people, has grown to more than 400 people. But our land has not grown. The land was small and there were many large hills, and we could not spread out as we would have liked, nor plant, hunt, or fish to maintain our traditional diet, which is essential for our health. There was also preserved forest there, which we could not disrupt, so there was no lowland left to make new gardens to plant.

Aldeia Verde was gtting too big, and the houses could no longer respect the moon shape of our traditional villages. The kuxex, the house where the pajés(5) sing with the yãmĩyxop, was very close to the houses and the women, who were not supposed to see inside, ended up seeing it, because they needed to cross the village to fetch water or visit relatives.

Donizete Maxakali

Few things make us sadder than the lack of fresh water in our territory. Without a river, we have nowhere to fish, nowhere to bathe, nowhere to wash our clothes or let the boiled cassava rest. Without a river, our children have nowhere to play and grow strong, which is why they get so sick. Without a river, our rituals are also impaired: our spirits have nowhere to bathe when they come to dance with us, nor do we, men and women, when we dress up to dance with them. The spirits were not coming to bathe the children like they used to; the monkey spirit was not bathing with the women as he used to; the yãmiyhex (women spirits) had nowhere to fish and the yãmĩyxop no longer came with their elephant spirit. The boys also had nowhere to bathe when the tatakox, the caterpillar spirits, took them to stay in the kuxex for a month without seeing their mothers and sisters. At the end of their resguardo,(6) couples did not have a river to blow and end the period as before.

Without a river, we had to consume water from the artesian wells that reached a few taps in the courtyard of some groups in Aldeia Verde, but the pump would always burn out and we would have no water for days on end. Also, the water often came out red, and its quality was not guaranteed. It is not part of our culture to bathe under a tap or shower only once or twice a day, as white people do. The dams that exist in the village are not good for bathing or drinking and, despite this, our children, with no alternative, ended up fishing and bathing in these lakes, catching many diseases and getting hurt on the wires that accumulated in the water, carried by the rains. We couldn’t go on living like that! We couldn’t tell our children not to bathe or not to fish. What does the government expect from us? That our children stay at home watching television and playing video games? We Tikmũ’ũn keep our language alive, our rituals alive, our stories and our songs alive! We are a hunting, farming and fishing people, and we want to continue to be like that.

The Tikmũ’ũn know how to heal the land. We can bring back the forest, the fruits, and the animals. When we arrived in Aldeia Verde, the forest was small. The farmers who lived there had burned everything to make charcoal and everywhere we saw nothing but grass. After we arrived, the forest grew again, but even so the land was very small. White people have few children these days, but we don’t. We have many children and one day our land will no longer fit so many people. Or are we all going to turn white and live in long cement houses like in the cities? Us living downstairs, our kids upstairs, our grandkids and our grandkids’ kids on top of them? And how are the yãmĩyxop going to get food, living in these houses? Are we going to have to take the elevator down to get food, or tie a very long vine to climb up, like monkeys, looking for food?

After much discussion, the Tikmũ’ũn group decided by majority: “Isael, Sueli, we have to look for another land, because in this small land there is no more room”. We decided to move, and we looked to the authorities to help us find the land. We searched for various Union and government lands but got none. Even so, we decided to leave Aldeia Verde in order to strengthen our culture.

We left Aldeia Verde when COVID-19 started, and we were worried about our pajés, who were threatened by the disease. We left and built another village close by, Aldeia Nova, New Village, where we stayed for a month. We talked to the mayor of Ladainha at the time and decided to sign a lease. We filled trucks and cars and moved. We settled near Ladainha, in an area where there was a large lagoon, but as soon as the next mayor was elected, a local newspaper reported that the lagoon could flood because of a nearby hydroelectric plant, which had structural problems, and that Aldeia Nova was at risk. We had to take quick action: either we went back to Aldeia Verde, or we looked for another terrain. We couldn’t even sleep well, searching and visiting various plot.

Our dream was to find good land for planting: we want to plant cassava, bananas, corn, beans… We don’t want to live off cestas básicas,(7) we have to work. Most of us rely on Bolsa Família,(8) and on governmental emergency aid, but we have seen that all of this can be cut and that we cannot rely on governments. Governments do not recognize that we are Indigenous people living in Minas Gerais and that our culture is still alive. They don’t recognize that our woods are alive, that they are people just like us, and that we need to raise their children so that the medicines from the forest and the water that makes our children grow strong like trees continue to exist.

Today, our pajés are tired and sad. They are hanging themselves; they are killing themselves so they don’t have to keep watching all the bad things that happen around here. The yãmĩyxop no longer have anywhere to hunt, bathe, or eat, because the forests and rivers are wasting away. They are worried. For this reason, the pajés often prefer to kill themselves. They think: “I’m going to go live with the yãmĩyxop and from there I’m going to take care of the Tikmũ’ũn!”. And so they do. They die, but they are still here, among us, walking through the woods, with the yãmĩyxop.

Totó Maxakali

We have been dreaming about land since 2005. This is the dream of the Aldeia-Escola-Floresta, our Village-School-Forest community. We visited several places; we lost count, and found nothing. Farmers don’t want to sell land to the Tikmũ’ũn, they don’t want to help Indigenous peoples. All this land, all the Mucuri Valley, was our territory, and that is why we say Nũhũ yãgmũ yõg hãm, “This land is ours”. That is the title of one of the movies we made. Today our land has borders and fences, and we cannot go beyond those. We can’t go to the city, because we suffer a lot of prejudice. We realized that we need to have a bigger land in order to be able to say: “This land belongs to our people, who are ancient people; this is where they have always been”.

Then we paid a visit to Itamunheque. We went, four of us, and eight leaders. We had a big meeting with the leaders, who are responsible for their families. Everyone liked the land and so we decided: in the early hours of September 28, 2021, almost 400 people from the Tikmũ’ũn people occupied the Fazenda de Itamunheque, in the municipality of Teófilo Otoni.

We hope to get this land back, to earn the right to it. The earth is alive, it speaks, it looks at us and screams, because it needs to be healed, it needs treatment. The farmers don’t listen to the land screaming, even though its cries for help. That’s why we want to reforest this land and make it the Village-School-Forest.

Where there is an Indigenous village, everywhere can be a classroom. Where there are trees and shade, we have a classroom. The children sing our rituals, they imitate the adults; on the riverbanks, they will play, sing and write on the sand. Everywhere is a classroom within the village. All the men go singing to the forest, they carry wood and sing. We named it Village-School-Forest because every village is a school. Where there is shade, women will gather and make handicrafts. The children listen alongside and learn too. Where there is a ritual shed, we have a real school, a very important one. In our village there will be singing, history, culture, traditional food.

We, the community of Aldeia-Escola-Floresta, are going to heal the land for the yãmĩyxop, for the children, for the future. We were all born together with the forest, we were all born together with the animals we hunt. This land is our mother because it feeds all of us, but when we got here the land was very dry, the branches had no leaves. We thought the trees were all drying up. Now we are organizing the land to plant tree seedlings, and fruit. We want to have a school, a health center to serve the community, and a headquarters for Funai.

We have to heal the land for the forest and for the river springs to return, because the forest produces water for us to drink. We also need our traditional foods back. We have to produce to supply the school, because today our students are eating non-Indigenous foods and becoming weak. Our youngsters need to have traditional foods for lunch. That’s why we are going to organize our school and we are going to plant a lot of crops here. We will plant cassava, beans, rice, bananas, sweet potatoes to supply this differentiated school.

We always said “differentiated school” when we talked about the school we wanted for our young ones, but we never managed to build it differently. Now the time has come for it to truly differentiate itself, for children to eat our traditional food and to learn our culture. We are concerned with our writing, our songs, our rituals, our painting, and our language, but we cannot forget our homes. We are concerned that young people do not know how to build their homes, that they take out loans to build with brick, with cement. The cement heats up, but our traditional houses are cool, the wind blows in at night. In the city, it is very hot because there is a lot of iron, cement, asphalt, and glass.

In the future, we will need a bigger land. Every year children are born and families grow, but our land remains the same. We cannot build one house on top of another. We must make houses on the ground. It is not our culture to build apartment buildings, and here we are preserving our culture. When we are old, we want to see the Village-School-Forest full of water springs, full of animals, gardens, trees, full of yãmĩyxop singing and painting themselves, full of our real houses, full of our children bathing, playing, and imitating the yãmĩyxop.

At Village-School-Forest we will have history, handicrafts, painting and ceramics as school subjects. Our dream is to hold pajés meetings, strengthen our culture, and think projects so that our Indigenous relatives, as well as non-Indigenous people, get to know us. We are going to have a cinema house with a big screen to show our culture, our films and films from other villages – from the Xingu, from the Guarani. We are going to give classes, and teach Indigenous students and also non-Indigenous ones. Non-Indigenous children will come to visit us, and our relatives from far away as well.

This is our dream, our Village-School-Forest, a project for wearing the skin of the earth and to protect it, reviving the territory for all animals, plants, rivers and for the yãmĩy; a project for taming the whites, children of ĩnmõxa – the hairy and ferocious beings who don’t wait, don’t talk, just grab the revolver –, to cure them of their exterminating voracity. This is our dream!

–

Isael Maxakali is a leader of the Village-School-Forest, artist and filmmaker. He belongs to Brazilian Tikmun’un (Maxakali) indigenous group. Along with Sueli Maxakali, he has produced a series of films, including the award-winning “Yãmĩyhex: As mulheres-espírito” (2019), “Nũhũ yãg mũ yõg hãm: Essa terra é nossa” (2020), and “Yãy tu nũnãhã payexop: Encontro de pajés” (2021). He won the PIPA Prize in 2020. He co-curated the exhibition “Mundos Indígenas” (2019), is a teacher in the Transversal Training in Traditional Knowledge Program at UFMG and holds an Honorary Doctorate in Communication from UFMG.

Sueli Maxakali is a leader of the Village-School-Forest, artist, filmmaker, and photographer. She belongs to Brazilian Tikmun’un (Maxakali) indigenous group. She co-curated the exhibition “Mundos Indígenas” (2019) and is a teacher in Transversal Training in Traditional Knowledge Program at UFMG. She co-directed the films “Quando os yãmiy vêm dançar conosco” (2011), “Yãmiyhex: as mulheres-espírito” (2019), and “Nũhũ yãgmũ yõg hãm: essa terra é nossa!” (2020). She published the photography book “Koxuk Xop Imagem” (2009) and holds an Honorary Doctorate in Literature from UFMG.

Donizete Maxakali, Totó Maxakali and Zé Antoninho Maxakali are artists and belong to Brazilian Tikmun’un (Maxakali) indigenous group.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese in the book Terra: antogia afro-indígena (PISEAGRAMA + UBU, 2023) and translated into English by Brena O’Dwyer.

How to quote

MAXAKALI, Isael; MAXAKALI, Sueli. Village-School-Forest. PISEAGRAMA Magazine. Online version, Read in English Section. Belo Horizonte, December 2023.

Notes

1 Botocudo is a generic denomination to Indigenous groups in the south of the state of Bahia, north of the states of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais.

2 Cachaça is a traditional Brazilian distilled liquor made from sugarcane.

3 In the context of Indigenous groups in Brazil, “demarcação de terra” or “land demarcation” specifically refers to the process of demarcating or delineating the boundaries of land that belongs to Indigenous communities. This process is essential for recognizing and protecting the land rights of Indigenous people and ensuring that they have legal ownership and control over their ancestral territories. The demarcation of Indigenous lands is a critical issue in Brazil, as it plays a crucial role in safeguarding the rights, culture, and way of life of Indigenous communities and helps protect these areas from encroachment and illegal activities.

4 Funai is an acronym for the Fundação Nacional do Índio, which translates as the “National Indian Foundation”. Funai is a government agency responsible for the protection and promotion of the rights of Indigenous peoples in Brazil.

5 A Pajé is an important person among Indigenous groups, they are healers who communicate with the spiritual realm.

6 Resguardo is a period of specific restrictions following certain life events, for example, childbirth.

7 Cesta básica is a term commonly used in in Brazil to refer to a package containing staple food. It consists of a collection of essential items and household goods that are considered necessary for a family, and typically include rice, beans, flour, cooking oil, sugar, milk, coffee, bread, and sometimes hygiene products like soap. Some governments or non-profit organizations may provide cestas básicas as part of social welfare programs or to assist those facing economic hardship.

8 Bolsa Família is an important social welfare program in Brazil, part of federal assistance programs. Bolsa Família provides financial aid to poor Brazilian families.